Why Liver Cancer Surveillance Matters in Cirrhosis

If you have cirrhosis, your risk of developing hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is much higher than the general population. In fact, more than 80% of HCC cases happen in people with advanced liver scarring. That’s not a small risk-it’s the leading cause of death for many with long-term liver disease. The good news? Catching HCC early can change everything. When tumors are found before they grow large or spread, treatments can actually cure the cancer. But if it’s found late, survival drops sharply. Surveillance isn’t optional-it’s life-saving.

Studies show that people who get regular screenings live longer. One major study found that those who underwent biannual ultrasounds had a 50-70% five-year survival rate, compared to just 10-20% for those who didn’t. That’s a massive difference. And it’s not just about living longer-it’s about living with quality. Early detection means less aggressive treatment, fewer side effects, and a better chance to keep working, traveling, or just enjoying time with family.

Who Should Be Screened and How Often

Not everyone with liver disease needs the same level of monitoring. The guidelines are clear: if you have cirrhosis, you should be screened every six months. That’s the standard across the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD), the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL), and most major medical bodies.

But here’s where it gets more nuanced. The EASL updated its stance in 2023 to recommend risk-based screening. That means if your annual risk of HCC is below 1.5%, you might not need routine scans. For example, someone with well-controlled hepatitis C after successful treatment and no other risk factors may fall into a lower-risk group. On the other hand, someone with ongoing alcohol use, diabetes, or hepatitis B has a much higher risk-sometimes over 5% per year-and needs strict, consistent monitoring.

Who gets screened? Typically:

- Adults with Child-Turcotte-Pugh (CTP) Class A or B cirrhosis

- Patients with hepatitis B and cirrhosis, regardless of viral load

- People with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) and advanced fibrosis

- Those with genetic liver diseases like hemochromatosis or alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency, if cirrhosis is present

CTP Class C cirrhosis is different. These patients often have severe liver failure and short life expectancy. Unless they’re on a transplant list, routine HCC screening isn’t recommended-because the focus shifts to comfort and quality of life, not cancer cure.

The Gold Standard: Ultrasound and Blood Tests

The main tool for HCC surveillance is abdominal ultrasound. It’s safe, cheap, and doesn’t use radiation. A good ultrasound can spot tumors as small as 1 cm. That’s critical-because at this size, curative options like surgery or ablation are still possible.

Ultrasound is done every six months. Why not yearly? Because HCC grows fast. On average, a tumor increases by 1-2 cm every six months in cirrhotic livers. Waiting a year could mean the difference between a treatable lump and an untreatable mass.

Many doctors also check a blood marker called alpha-fetoprotein (AFP). But here’s the catch: AFP isn’t reliable on its own. About 30-40% of early HCC cases have normal AFP levels. That’s why guidelines only conditionally recommend it. An AFP above 20 ng/mL (or 20 μg/L) should trigger further imaging-but a normal AFP doesn’t rule out cancer. Think of AFP as a supporting actor, not the lead.

What Happens When Something Shows Up?

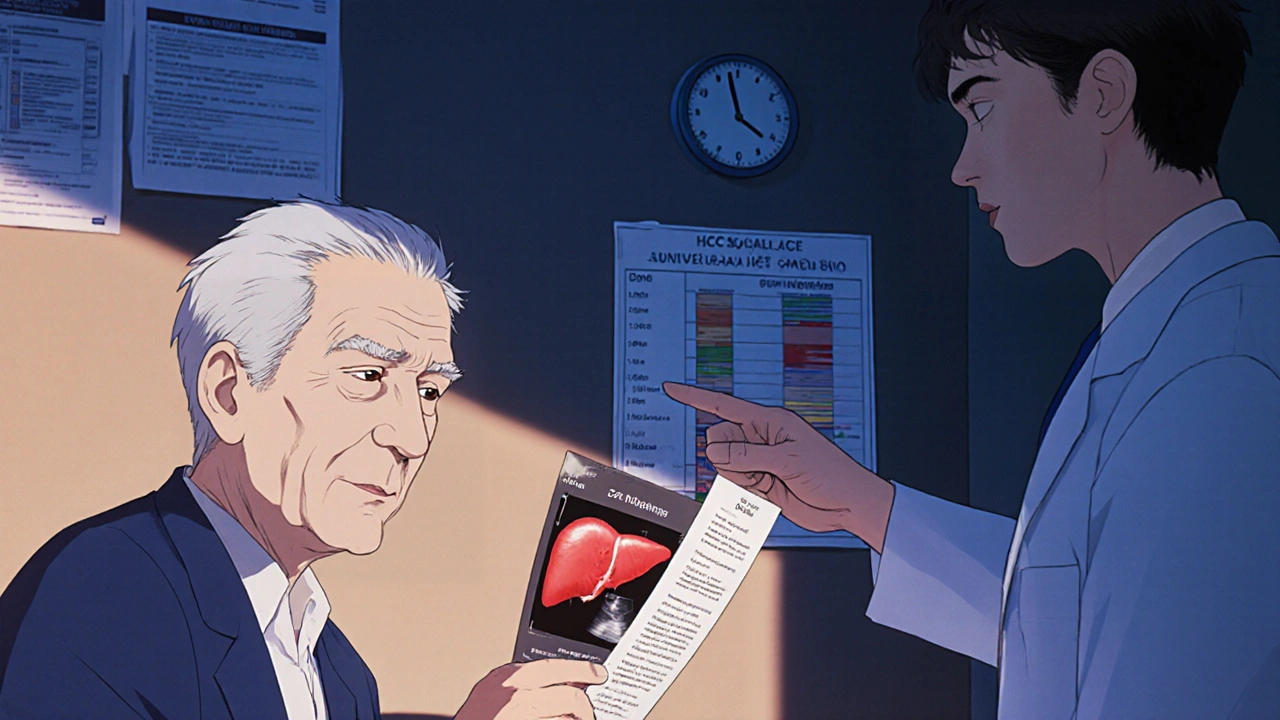

If your ultrasound finds a mass larger than 1 cm-or your AFP spikes-you won’t wait. You’ll be sent for a multiphase contrast scan: either a CT or MRI of the liver. These scans look at how the tumor takes up contrast dye over time, which helps tell if it’s cancer.

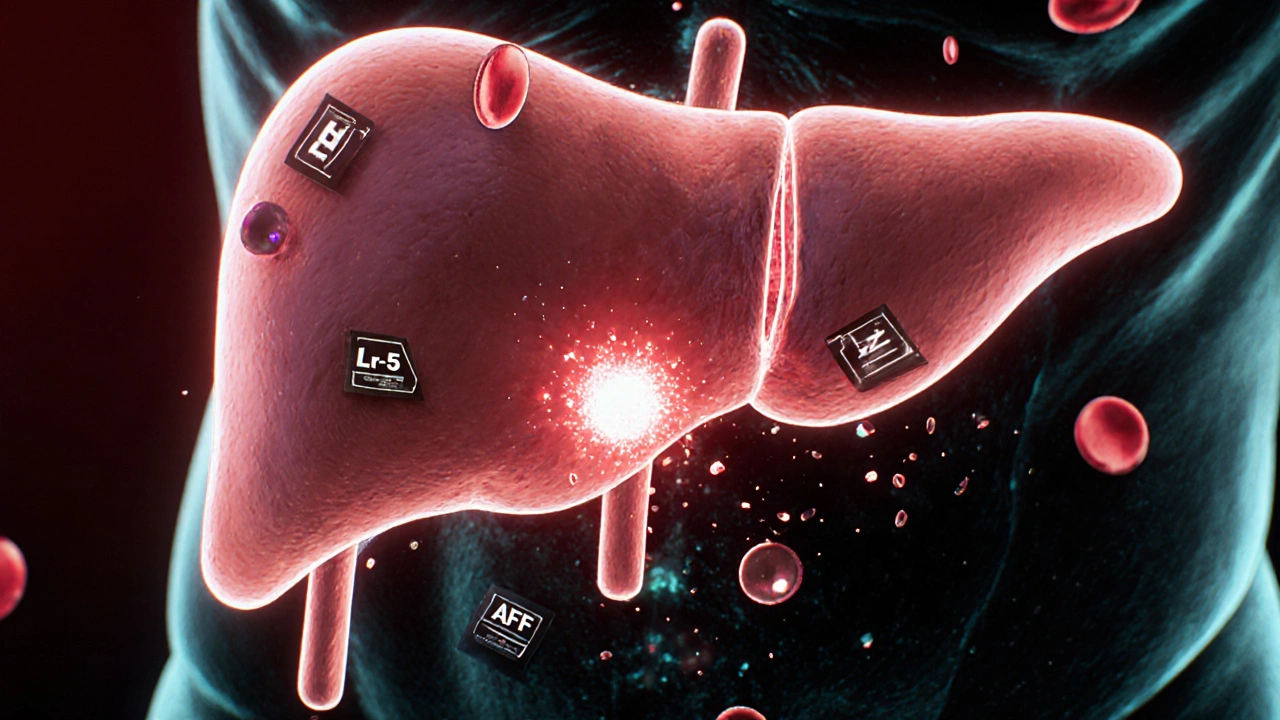

The American College of Radiology’s LI-RADS system is now the global standard for interpreting these scans. It classifies liver lesions from LR-1 (definitely benign) to LR-5 (definitely HCC). A score of LR-5 means no biopsy is needed-you can move straight to treatment. Even LR-4 lesions, which are probably cancer, often proceed to treatment without biopsy if the imaging is clear and the patient has cirrhosis.

This is a big shift from the past. In the old days, every liver nodule got biopsied. Now, we rely on imaging patterns. Why? Because biopsies can miss cancer, cause bleeding, or even spread tumor cells. Imaging is faster, safer, and just as accurate in the right context.

Treatment Options: From Cure to Control

Once HCC is confirmed, treatment depends on three things: tumor size and number, liver function, and whether the cancer has spread.

Early-stage HCC (BCLC Stage 0 or A): This is where cure is still possible.

- Surgical resection: Removing the tumor. Best for patients with good liver function and one small tumor.

- Liver transplant: The best long-term option if you qualify. Removes both the cancer and the diseased liver. But you need to be on a waiting list, and organs are limited.

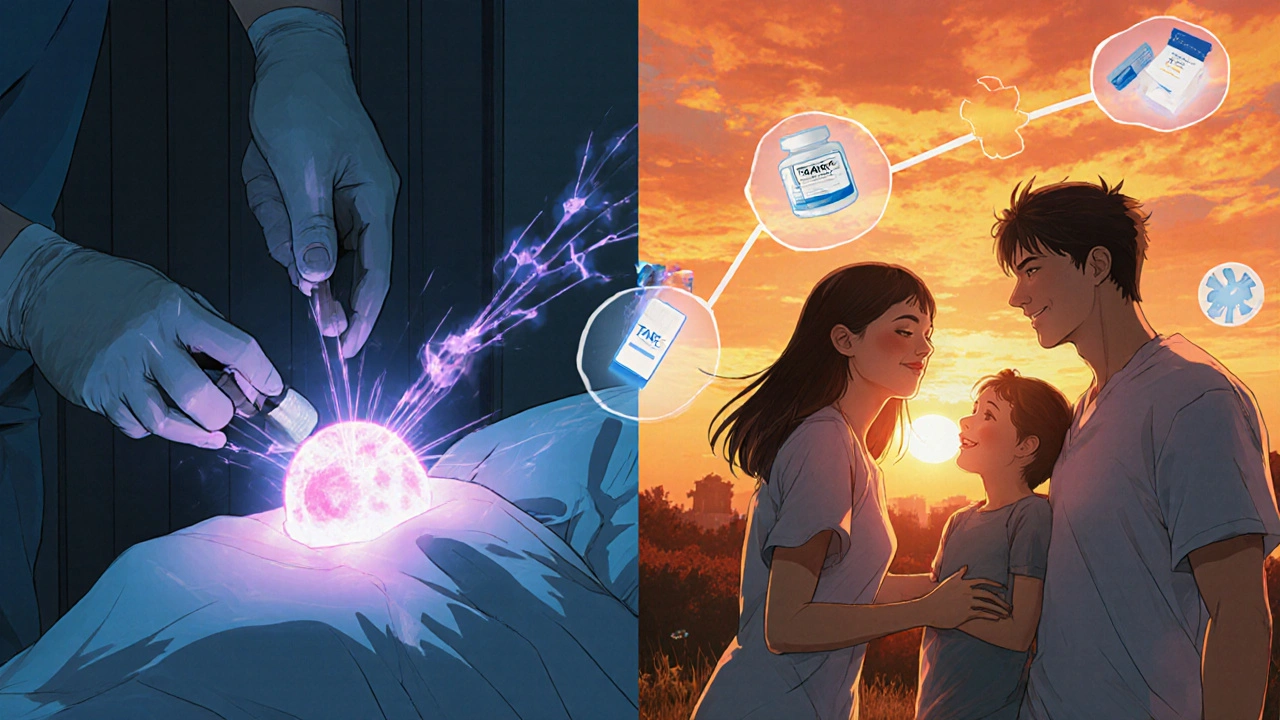

- Ablation: Using heat (radiofrequency) or cold (cryoablation) to destroy the tumor. Done through the skin, no major surgery. Works well for tumors under 3 cm.

Intermediate-stage HCC (BCLC Stage B): Multiple tumors, but still confined to the liver.

- Transarterial chemoembolization (TACE): A catheter delivers chemo directly to the tumor and blocks its blood supply. Repeated every few months.

- Transarterial radioembolization (TARE): Uses radioactive beads instead of chemo. Often used if TACE isn’t effective.

Advanced-stage HCC (BCLC Stage C): Cancer has spread to blood vessels or other organs.

- Targeted therapy: Drugs like sorafenib, lenvatinib, or cabozantinib slow tumor growth by blocking signals cancer cells need to survive.

- Immunotherapy: Drugs like nivolumab or pembrolizumab help your immune system recognize and attack cancer cells. Often combined with bevacizumab (a blood vessel blocker).

- Combination regimens: The new standard for many patients is immunotherapy + targeted therapy. Trials show this combo improves survival by months, sometimes over a year.

For those with very advanced disease and poor liver function, the focus shifts to palliative care-managing pain, fluid buildup, and fatigue. The goal isn’t cure anymore. It’s comfort.

Why So Many People Miss Screening

Even though the guidelines are clear, most people with cirrhosis never get screened. In the U.S., only about 40% of eligible patients receive regular ultrasounds. Why?

- Provider gaps: Many primary care doctors don’t know when or how to refer. One study found only 45% of hepatology clinics have formal screening pathways.

- Patient barriers: Missed appointments are common-25-40% of people don’t show up for scans. Transportation, cost, fear, and confusion all play a role.

- System issues: No automated reminders in electronic records? That’s a huge problem. One VA study showed reminders increased screening rates from 35% to 68%.

- Disparities: Black patients and those on Medicaid are half as likely to get screened as white, privately insured patients. This isn’t about health-it’s about access.

Successful programs fix these gaps. They use patient navigators to call and remind people. They embed screening into routine liver clinic visits. They train ultrasound techs specifically in liver imaging. And they use AI tools-like Medtronic’s LiverAssist-to help detect tiny tumors that human eyes might miss.

The Future: Biomarkers, AI, and Personalized Screening

The next big leap in HCC detection isn’t just better ultrasounds-it’s smarter screening. Researchers are testing new blood tests that detect cancer before it shows up on imaging.

The GALAD score combines age, gender, AFP, AFP-L3, and DCP (des-gamma-carboxy prothrombin). It’s already detecting early HCC with 85% accuracy. Another tool, the aMAP score (based on age, gender, albumin, bilirubin, platelets), can predict risk with 81% accuracy. These aren’t replacements for ultrasound yet-but they could become supplements, especially for high-risk patients.

By 2027, abbreviated MRI scans (done in under 7 minutes) may replace ultrasound for high-risk patients. The cost is dropping-down to $350-$400-and the image quality is far better. MRI can spot tumors under 1 cm with 90% accuracy, while ultrasound misses up to 20% of those.

And the big trial? The SURVIVE study, tracking 10,000 cirrhotic patients, is comparing standard screening to risk-based screening. Results are due by late 2025. If it proves risk-based screening saves lives and cuts costs, guidelines will change overnight.

What You Can Do Right Now

If you have cirrhosis:

- Ask your doctor: “Am I on a liver cancer screening schedule?”

- Confirm you’re getting an ultrasound every 6 months-not yearly.

- Ask if your center uses LI-RADS for interpreting scans.

- If you miss an appointment, reschedule immediately. Delaying by months can be dangerous.

- Know your liver function score (Child-Pugh class). It affects your treatment options.

If you’re a caregiver or family member: Help track appointments. Drive them. Ask questions. This isn’t something to leave to chance.

Early detection saves lives. It’s not magic. It’s medicine. And it’s available-if you know to ask for it.

Is hepatitis B or C the main cause of liver cancer?

Hepatitis B and C are major causes, but not the only ones. In the U.S., non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is now the fastest-growing cause of HCC, especially in people with obesity or diabetes. Hepatitis B causes more cancer in Asia and Africa, while hepatitis C used to be the top cause in the West-until direct-acting antivirals made it curable. Even after curing hepatitis C, if cirrhosis is already present, HCC risk remains.

Can you get liver cancer without cirrhosis?

Yes, but it’s rare-only about 10-20% of HCC cases occur in people without cirrhosis. These cases are often linked to chronic hepatitis B, exposure to aflatoxins (a mold found in poorly stored grains), or rare genetic conditions. For most people, cirrhosis is the essential first step. That’s why screening focuses on cirrhotic patients.

Does alcohol cause liver cancer even if I don’t have cirrhosis?

Heavy alcohol use increases your risk of HCC, but mostly because it leads to cirrhosis. If you drink heavily and have no liver scarring, your cancer risk is still low. But if you have even mild fibrosis, your risk jumps. Cutting back or stopping alcohol is one of the most effective ways to reduce your HCC risk, even after diagnosis.

How often should I get an ultrasound if I have cirrhosis?

Every six months. That’s the standard for all major guidelines. Waiting longer increases the chance your tumor will grow beyond the point where it can be cured. Some high-risk patients (like those with active hepatitis B or diabetes) may be offered MRI every 6 months instead, but ultrasound remains the first-line tool for most.

Is liver cancer screening covered by insurance?

Yes, in most cases. Medicare, Medicaid, and private insurers cover biannual abdominal ultrasounds for patients with documented cirrhosis. Some plans require a referral from a specialist. If you’re being denied coverage, ask for a copy of the AASLD or EASL guidelines to support your case. Screening is considered a preventive service under U.S. healthcare policy for high-risk groups.

Can liver cancer come back after treatment?

Yes. Even after successful removal or ablation of a tumor, new cancers can develop in the scarred liver. That’s why lifelong surveillance continues-even after treatment. The liver doesn’t heal completely after cirrhosis. New cancer cells can form anywhere in the damaged tissue. Regular scans are needed for life, not just until the first tumor is gone.

Alyssa Torres

November 19, 2025 AT 15:10I just got diagnosed with cirrhosis last month, and I swear I almost cried reading this. I’ve been skipping my ultrasounds because I’m scared of what they might find. But now? I’m scheduling mine for next week. This post didn’t just inform me-it gave me a reason to fight. Thank you.

Summer Joy

November 20, 2025 AT 00:11OMG I can’t believe people still think AFP is reliable?? 😤 Like bro, it’s literally worse than a horoscope. I work in radiology and we stopped using it as a standalone 5 years ago. If your doc is still ordering it without imaging? Run. 🏃♀️💨

Aruna Urban Planner

November 20, 2025 AT 11:51From India, where access to even basic ultrasound is a luxury for many, this article hits differently. The GALAD and aMAP scores? They’re not just science-they’re lifelines for populations without imaging infrastructure. We need these biomarkers scaled locally, not just in academic journals. Screening shouldn’t be a privilege of wealth.

Also, the LI-RADS system is brilliant, but without trained radiologists in rural clinics, it’s just a checklist. Training community health workers to interpret basic ultrasound patterns could bridge the gap. Not perfect-but pragmatic.

Nicole Ziegler

November 22, 2025 AT 09:41Just got my 6-month ultrasound today 🎉 and they found nothing! Still waiting on AFP results but honestly? I’m already celebrating. This post reminded me to not skip appointments. Also, my dog got a treat today too 🐶💕

Bharat Alasandi

November 23, 2025 AT 00:55Bro, in India we got no access to MRI or TACE. Most of us get ultrasounds every year if we’re lucky. But I read this and realized-I’m not just a patient, I’m a data point. I’m gonna start pushing my local clinic for LI-RADS. Even if they don’t have the fancy machines, they can at least follow the protocol.

Also, the part about cirrhosis = lifelong screening? Yeah. My uncle died because they stopped after his first tumor. Don’t let that happen to you.

Kristi Bennardo

November 23, 2025 AT 11:23This article is dangerously oversimplified. You imply that all cirrhotic patients should be screened without acknowledging the cost-benefit analysis in low-resource settings. You ignore the psychological trauma of false positives. You dismiss Child-Pugh C patients as ‘not worth saving’-that’s eugenics dressed as medicine. This isn’t public health. It’s corporate-driven screening theater.

Shiv Karan Singh

November 24, 2025 AT 17:40LMAO surveillance? Nah. I’ve seen 3 cirrhotic guys die after getting screened. One got a biopsy, bled out. Another had a false LR-5, got a transplant, died waiting. The system is rigged. You think they care if you live? They care if you pay for the scan. And don’t even get me started on AI tools-those are just pharma’s way to sell more software.

Real talk: stop scanning. Start drinking less. And if you’ve got cirrhosis? Accept it. Life’s not fair. 😎

Ravi boy

November 26, 2025 AT 05:35my cousin in delhi got hcc last year no screening at all he just felt pain then boom. ultrasound here costs 2000 rs and no one has insurance. i think we need mobile vans with portable usg like they do for pap smears. also why no one talks about aflatoxin in rice and peanuts? its everywhere here and no one checks

Matthew Karrs

November 27, 2025 AT 18:35They’re lying about the 50-70% survival rate. That’s only if you’re white, insured, and live near a university hospital. My cousin had cirrhosis, got screened, got a tumor, got TACE-then got denied insurance renewal. He died six months later. The system doesn’t want you cured. It wants you monitored, billed, and scared enough to keep coming back.