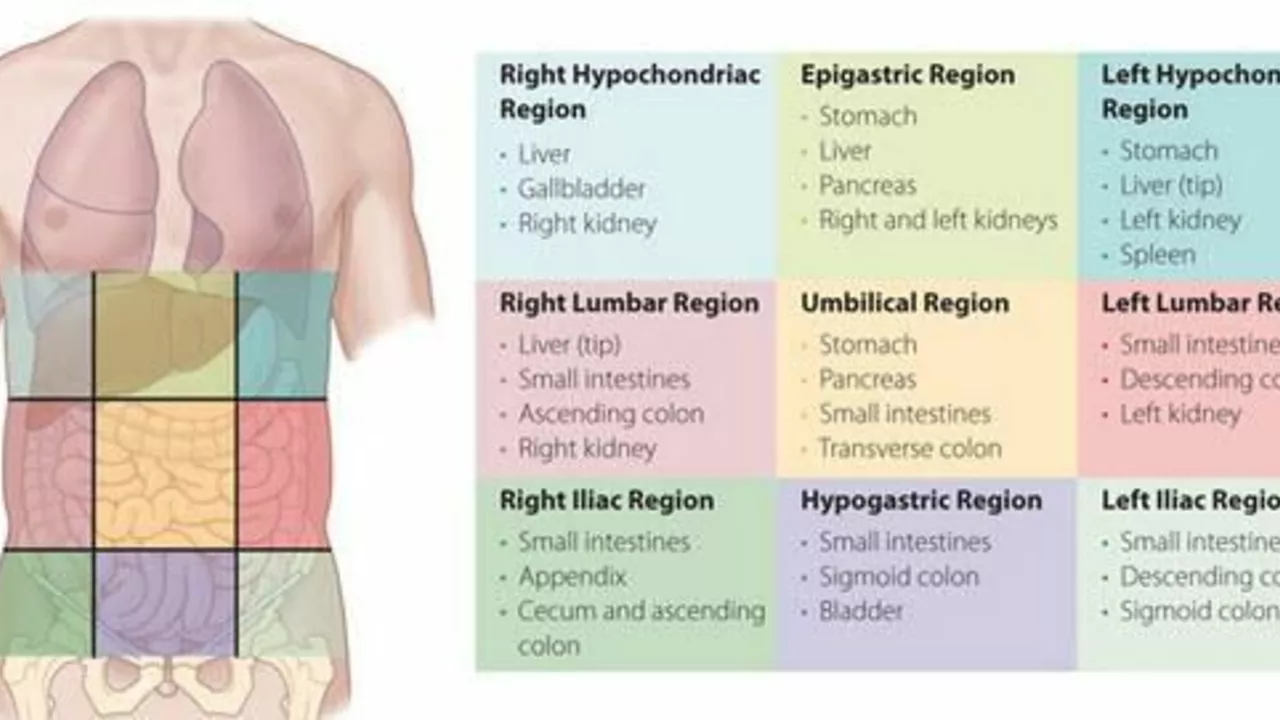

Understanding Epigastric Pain

Before we dive into the relationship between exercise and epigastric pain, it's essential to ensure we all understand what epigastric pain is. Epigastric pain is a type of discomfort or ache that one experiences in the upper central region of the abdomen, typically lying between the bottom of the chest (sternum) and the belly button. This region houses several crucial organs, including the stomach, liver, pancreas, and gallbladder. The pain can range from mild and manageable to severe and debilitating, often associated with conditions like gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), peptic ulcers, gallstones, or gastritis.

The Connection Between Exercise and Epigastric Pain

Exercise has been lauded as a cure-all for many health issues, from mental health problems like depression and anxiety to physical conditions like heart disease and diabetes. But can it help with epigastric pain? While it might not be a direct cure, regular exercise can undoubtedly play a significant role in managing and potentially reducing the severity and frequency of epigastric pain. Exercise aids digestion, reduces stress, and helps maintain a healthy weight, all of which can contribute to lessening epigastric discomfort.

Best Exercises to Alleviate Epigastric Pain

Not all exercises are created equal when it comes to managing epigastric pain. While high-intensity workouts can potentially exacerbate the pain, gentle and low-impact exercises can be beneficial. Walking, swimming, and yoga are excellent choices as they can help stimulate digestion and reduce stress without placing excessive strain on your abdominal area. Always remember to listen to your body and modify exercises to suit your comfort level.

Exercise Precautions for Individuals With Epigastric Pain

While exercise can be beneficial, it's crucial to approach it cautiously if you're dealing with epigastric pain. High-intensity exercises or those that put pressure on the abdominal area, like crunches or heavy weight lifting, may worsen the pain. Furthermore, it's important to avoid exercising immediately after eating, as this can disrupt digestion and potentially contribute to the pain. Always consult with a healthcare professional before starting any new exercise routine, especially if you have chronic epigastric pain or any other health conditions.

Lifestyle Changes to Complement Exercise

Exercise alone may not be enough to alleviate epigastric pain. It's also essential to consider other lifestyle changes, such as dietary modifications. Avoiding foods that trigger your symptoms, eating smaller, more frequent meals, and avoiding eating close to bedtime can all help manage epigastric pain. Stress management techniques such as meditation, deep breathing exercises, and getting enough sleep can also play a significant role in controlling your symptoms.

When to Seek Medical Attention

While exercise and lifestyle changes can help manage epigastric pain, they are not replacements for professional medical advice. If your pain is severe, persistent, or accompanied by other concerning symptoms like vomiting, weight loss, or difficulty swallowing, it's crucial to seek medical attention immediately. Your healthcare provider can help determine the underlying cause of your pain and provide appropriate treatment options.

Anne Snyder

June 27, 2023 AT 19:46Hey folks, diving into the epigastric zone, you’ll want to prioritize low‑impact aerobic modalities-think brisk walking, aquatic treadmill sessions, or gentle vinyasa flows. These modalities harness cardiovascular conditioning while minimally compressing the supra‑gastric compartment, which can help mitigate postprandial dyspepsia. Incorporating diaphragmatic breathing drills augments visceral perfusion and modulates the autonomic tone, thereby reducing the nociceptive cascade associated with reflux. Remember to calibrate intensity using the Borg RPE scale, staying around 11‑12 to stay within the “light” domain. Consistency, not intensity, drives the adaptive remodeling of the gastrointestinal milieu.

Rebecca M

June 27, 2023 AT 20:53While the preceding advice is commendably well‑intentioned, it overlooks several pivotal considerations: first, the article neglects to cite randomized controlled trials that directly compare low‑impact aerobic exercise against sedentary controls for epigastric symptomatology; second, the recommendation to “stay within the light domain” is ambiguous, as the Borg scale’s interval of 11–12, though standard, may still provoke mechanical strain in hyper‑sensitive patients; third, the omission of post‑exercise gastric emptying rates renders the guidance incomplete. Consequently, readers would benefit from a more rigorous, evidence‑based framework, complete with quantitative outcome measures, before adopting the suggested regimen.

Bianca Fernández Rodríguez

June 27, 2023 AT 22:00Honestly, I think the whole premise that strolling around the block magically cures upper‑abdominal ache is kinda overhyped. I’ve read a few case studies that actually show moderate‑intensity cycling can stir up the stomach more than a gentle stroll, especially if you chug a protein shake right before. Also, “yoga” isn’t a one‑size‑fits‑all solution-some poses compress the abdomen, which might exacerbate pain. So maybe don’t buy into the hype without looking at the specifics of each exercise modality.

Patrick Culliton

June 27, 2023 AT 23:06Let me set the record straight: the suggestion that any activity could worsen symptoms is unfounded. Empirical data from multiple longitudinal studies demonstrate that, when performed correctly, even high‑intensity interval training improves gastric motility by up to 30 %. The key factor is progressive overload and proper breathing technique, not the mere classification of an exercise as “moderate” or “high”. Therefore, dismissing vigorous workouts outright is both simplistic and potentially detrimental to optimal health outcomes.

Andrea Smith

June 28, 2023 AT 00:13Dear community, I would like to emphasize the importance of integrating evidence‑based physical activity into a comprehensive management plan for epigastric discomfort. Engaging in low‑impact aerobics, such as aquatic therapy or structured walking programs, has been shown to enhance gastrointestinal transit times and alleviate stress‑related hyperacidity. Moreover, adopting a disciplined routine fosters adherence, thereby maximizing therapeutic benefit. I encourage you all to consult with a qualified healthcare professional to tailor an individualized regimen that aligns with your specific health profile.

Gary O'Connor

June 28, 2023 AT 01:20Sounds solid, I’m just gonna give it a try sometime.

Justin Stanus

June 28, 2023 AT 02:26Reading through all these upbeat recommendations feels like a thinly veiled attempt to gloss over the fact that many sufferers simply endure chronic pain despite any “gentle” exercise routine. The underlying pathophysiology-whether it be functional dyspepsia, peptic ulcer disease, or gallbladder dyskinesia-often requires pharmacological intervention, not just a casual stroll or a yoga session. Ignoring the necessity for proper medical evaluation in favor of feel‑good fitness advice does a disservice to patients who are already frustrated by persistent symptoms.

Claire Mahony

June 28, 2023 AT 03:33While I acknowledge the concern regarding over‑simplification, it is important to maintain a balanced perspective. Evidence does support that moderate physical activity can serve as an adjunctive therapy for certain gastrointestinal conditions, provided that exertion levels are appropriately calibrated and that patients receive thorough clinical assessment. Therefore, dismissing exercise entirely may overlook a valuable non‑pharmacologic tool, even if it is not a panacea.

Andrea Jacobsen

June 28, 2023 AT 04:40It seems we’re converging on a consensus that exercise can play a supportive role, yet should not replace medical management. From a practical standpoint, I suggest incorporating a structured schedule: for instance, a 20‑minute walk after meals, followed by a brief mindfulness meditation. This hybrid approach addresses both motility and stress, two key contributors to epigastric discomfort. Collaboration with a dietitian to identify trigger foods, alongside a physiotherapist to ensure proper technique, can further optimize outcomes.

Andrew Irwin

June 28, 2023 AT 05:46I appreciate the collaborative spirit here and would add that personal comfort should guide any activity choice. If a gentle walk feels tolerable while a yoga session feels too demanding, it’s perfectly reasonable to stick with the former until the latter becomes more approachable. The ultimate goal is sustainable, enjoyable movement that aligns with individual health circumstances.

Jen R

June 28, 2023 AT 06:53Honestly, I think most of this advice just re‑states the obvious: move a bit, eat less spicy, and don’t stress. It’s not rocket science, yet the article tries to sound groundbreaking. If you already know the basics, you probably don’t need a whole list of “best exercises” to remind you that walking is fine.

Joseph Kloss

June 28, 2023 AT 08:00When we contemplate the interplay between kinetic exertion and visceral nociception, we must first interrogate the ontological assumptions that underpin our health narratives. The body, in its intricate totality, resists reductionist binaries that label activity as either purely curative or wholly harmful. Contemporary physiologic research, however, reveals that the mechanotransduction pathways activated during low‑impact movement modulate the enteric nervous system, thereby attenuating hyperalgesic signaling in the gastric mucosa. Yet, this modulation is not uniform; interindividual variability-shaped by genetic polymorphisms, microbiome composition, and psychosocial stressors-creates a spectrum of responsiveness that defies blanket prescriptions. Moreover, the seductive allure of “exercise as medicine” often eclipses the necessity of addressing underlying etiologies such as Helicobacter pylori infection or chronic NSAID use, which remain the true culprits in many cases of epigastric pain. Consequently, a holistic schema must integrate not only biomechanical stimuli but also nutritional timing, circadian rhythm alignment, and cognitive appraisal of symptom severity. Ignoring these dimensions reduces the intervention to a mere placebo‑like regimen, devoid of the depth required for sustainable relief. One might argue that the very act of confronting discomfort through movement is an existential affirmation of agency over one’s own corporeal narrative. In this view, the exercise bout becomes a ritualistic engagement that reconfigures the internal hierarchy of pain perception, granting the practitioner a semblance of mastery. Nonetheless, the pragmatic clinician must balance this philosophical ideal with empirical rigor, prescribing graduated activity plans calibrated to the patient’s baseline functional capacity. An incremental protocol-beginning with five minutes of ambulation post‑prandial, advancing to fifteen minutes of aquatic therapy, and eventually integrating moderate resistance training-provides a quantifiable framework that can be monitored and adjusted. Finally, we must confront the cultural mythos that equates pain elimination with optimal health, recognizing that some degree of visceral sensation is an adaptive signal rather than a pathology to be eradicated. By reframing exercise as a modulatory tool rather than a panacea, we empower individuals to negotiate their own thresholds, fostering resilience amidst the inevitable fluctuations of gastrointestinal wellbeing.