When a brand-name drug loses its patent, the first generic version hits the market-and prices usually drop by about 13%. That sounds good. But here’s the real story: the biggest savings don’t come from the first generic. They come from the second and third ones.

Why the second generic changes everything

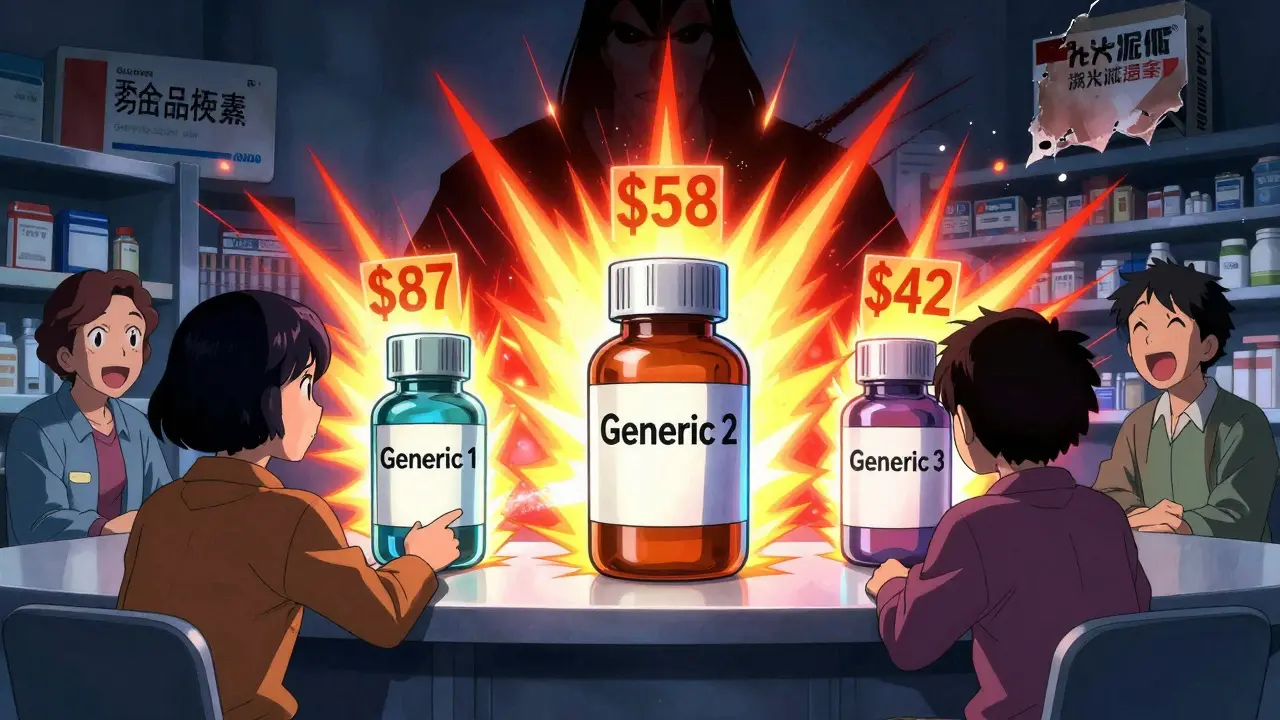

The first generic manufacturer doesn’t have to compete with anyone else. They can charge just enough less than the brand to attract customers, but still make a healthy profit. In most cases, that first generic sells for about 87% of the original brand price. For a $100 pill, that’s still $87. Not exactly a bargain. But as soon as a second company gets FDA approval and starts selling the same drug, everything shifts. Suddenly, two manufacturers are fighting for the same customers. That’s when prices start to really fall. Studies show that the second generic typically drops the price to about 58% of the brand’s original cost. That same $100 pill now costs $58. That’s a 31% drop in just one step. This isn’t guesswork. The FDA tracked over 2,400 generic drugs approved between 2018 and 2020. Their data shows this pattern holds across dozens of medications-from blood pressure pills to antibiotics to diabetes treatments. The moment a second manufacturer enters, the market flips from a monopoly to a duopoly. And in a duopoly, neither company can afford to hold prices high. They undercut each other. And patients win.The third generic is where the real savings kick in

Now imagine a third company joins the race. That’s when the price drops even further-to around 42% of the brand’s original price. For our $100 pill, that’s $42. That’s a 58% discount compared to the brand, and a 27% drop from the second generic alone. The FDA found that adding a third generic doesn’t just help a little-it unlocks the biggest chunk of savings. In markets with three or more competitors, prices keep falling for years. By the time five or six generics are available, some drugs cost less than 20% of the original brand price. In rare cases, like the cholesterol drug simvastatin, prices fell over 90% after a dozen manufacturers entered the market. This isn’t theoretical. In 2021, the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation at HHS analyzed real-world data from 2016 to 2019. They found that when a drug had three generic manufacturers, prices dropped by an average of 20% compared to two. With five or more, prices fell by 60-80%. The sweet spot? Between the second and fifth generic entrant. After that, the market can get unstable-some manufacturers exit, others consolidate, and prices can spike again.What happens when competition stalls

Here’s the problem: a lot of generic markets never get past two manufacturers. Nearly half of all generic drugs in the U.S. operate in duopolies, according to a 2017 University of Florida study. That means millions of patients are stuck paying higher prices than they should. And when competition drops-from three manufacturers to two-prices don’t just stop falling. They often go up. The same University of Florida study found that when one manufacturer exits a three-way market, prices can jump 100% to 300%. That’s not a coincidence. It’s a market failure. With fewer players, there’s less pressure to cut prices. Companies start matching each other’s prices instead of undercutting them. That’s called tacit collusion. And it’s happening more often. Why? Because the generic drug market isn’t just about manufacturers. It’s controlled by three giant wholesalers-McKesson, AmerisourceBergen, and Cardinal Health-who handle 85% of all generic drug distribution. And three pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs)-Express Scripts, CVS Health, and Humana-control 80% of prescription processing. These middlemen have enormous power. They can choose which generics to push to pharmacies, and which to bury in fine print. If they favor one manufacturer over others, they can block new entrants-even if those new companies have FDA approval.

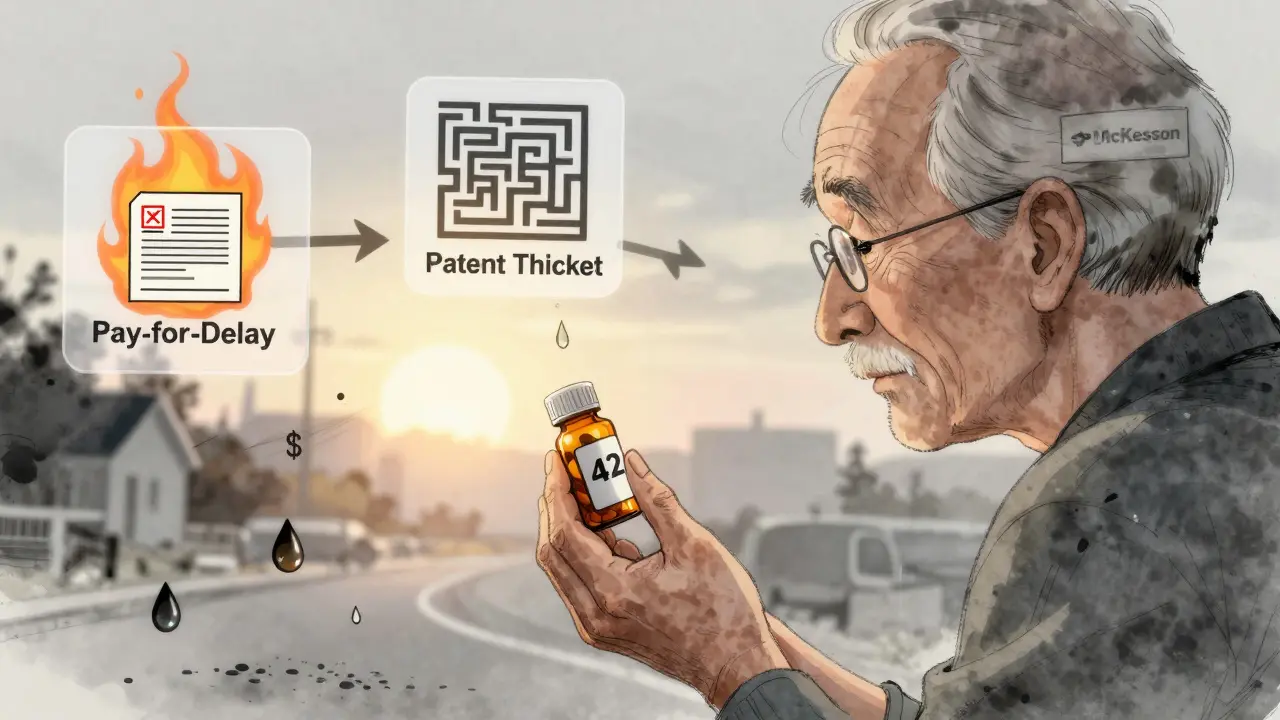

How anti-competitive tactics block savings

Brand-name drugmakers don’t give up easily. Even after their patent expires, they use tricks to delay generic competition. One common tactic is called “pay for delay.” A brand company pays a generic manufacturer to stay out of the market. In exchange, the generic company gets a cut of the brand’s profits. These deals cost patients and taxpayers billions. The Blue Cross Blue Shield Association estimates they add $12 billion a year to drug costs-$3 billion of that comes out of patients’ pockets. Another trick is “patent thicketing.” A brand company files dozens of minor patents on the same drug-covering everything from pill shape to packaging. Even if the core patent expires, these secondary patents can block generics for years. One drug had 75 patents, extending its monopoly from 2016 to 2034. That’s not innovation. That’s legal obstruction. The FDA and Congress have tried to fix this. The CREATES Act (2022) makes it harder for brand companies to refuse to sell samples to generic makers-a common tactic to delay approval. The Preserve Access to Affordable Generics Act targets pay-for-delay deals. And the FDA’s GDUFA III program (2023-2027) is speeding up reviews for complex generics, where competition has been slow to arrive.Why this matters for everyday patients

These aren’t abstract economic theories. They’re real dollars in people’s wallets. Between 2018 and 2020, the entry of new generic drugs saved American patients $265 billion. That’s not a rounding error. That’s enough to cover the cost of insulin for every diabetic in the country for over a year. For someone on a fixed income, a $42 pill instead of a $100 pill means they can afford their medication month after month. For a family managing multiple prescriptions, it means choosing between medicine and groceries. For Medicare, it means billions saved every year-money that could go toward better care for seniors. But savings only happen if competition is allowed to work. If the second or third generic is blocked by a pay-for-delay deal, or if a PBM refuses to include a new manufacturer on its formulary, those savings vanish. And patients pay the price.

What’s next for generic drug pricing

Looking ahead, experts predict generic prices will keep falling-by 3% to 5% a year through 2027. But that’s only if enough manufacturers keep entering the market. If consolidation continues-like the merger of Mylan and Upjohn into Viatris, or Teva buying Allergan’s generics division-there will be fewer independent players. Fewer players mean less competition. Less competition means higher prices. The Congressional Budget Office warns that without stronger enforcement against anti-competitive practices, Medicare could lose $25 billion annually by 2030. That’s money that could be spent on patient care, not wasted on inflated drug prices. The bottom line? The second and third generic entrants are the most powerful tool we have to lower drug costs. Not legislation. Not negotiation. Not brand-name rebates. Just competition. When two or three companies make the same drug, they don’t need to be told to lower prices. They do it on their own. That’s how free markets are supposed to work.What you can do

If you’re on a generic medication, ask your pharmacist: “How many manufacturers make this drug?” If they say one or two, ask if there’s another version available. Sometimes, switching to a different generic brand-even if it’s the same active ingredient-can save you money. If your insurance denies coverage for a newer generic, file an appeal. Insurers are required to cover FDA-approved drugs. If they don’t, they may be following PBM formularies that favor older or more profitable manufacturers. And if you know someone who can’t afford their meds, share this: the cheapest version isn’t always the one you see first. The real savings come when more companies join the race.Why do generic drug prices keep dropping after the first one enters?

The first generic usually doesn’t drop prices dramatically because there’s no competition. But when a second company enters, they undercut the first to win market share. The third company pushes prices even lower to compete with both. This creates a chain reaction where each new entrant forces everyone to lower prices to stay in the game.

How much can I save if my drug has three generic manufacturers?

On average, a drug with three generic manufacturers costs about 42% of the original brand price. That’s roughly a 58% discount. For example, if the brand cost $100, you’d pay about $42. Some drugs drop even lower-down to $20 or less-when five or more companies make them.

Why aren’t there more generic manufacturers for some drugs?

Some drugs are hard or expensive to make-like complex injectables or inhalers. Others face delays because brand companies block access to samples or file endless patents. Also, a few big companies control most of the market, so smaller manufacturers can’t compete. And PBMs often favor certain brands, making it harder for new ones to get into pharmacies.

Do generic drugs work the same as brand-name drugs?

Yes. The FDA requires all generics to have the same active ingredient, strength, dosage form, and route of administration as the brand. They must also meet the same strict standards for safety, purity, and effectiveness. The only differences are in inactive ingredients-like fillers or dyes-which don’t affect how the drug works.

Can I ask my doctor to prescribe a specific generic brand?

Yes. Your doctor can write "dispense as written" or specify a manufacturer on the prescription. But in most cases, pharmacies will choose the cheapest option unless you ask for something specific. If you’re paying out of pocket, ask your pharmacist which generic is the lowest priced. Sometimes the difference is $20 a month.

Jamie Hooper

January 24, 2026 AT 14:11Luke Davidson

January 25, 2026 AT 21:48Himanshu Singh

January 25, 2026 AT 23:19Vatsal Patel

January 27, 2026 AT 12:11Sawyer Vitela

January 29, 2026 AT 11:21Shanta Blank

January 30, 2026 AT 05:08Dolores Rider

January 30, 2026 AT 08:41Viola Li

January 30, 2026 AT 08:48asa MNG

January 30, 2026 AT 11:13Jenna Allison

January 31, 2026 AT 15:17Sharon Biggins

February 2, 2026 AT 12:51venkatesh karumanchi

February 2, 2026 AT 20:46Patrick Gornik

February 3, 2026 AT 15:17Karen Conlin

February 4, 2026 AT 06:32