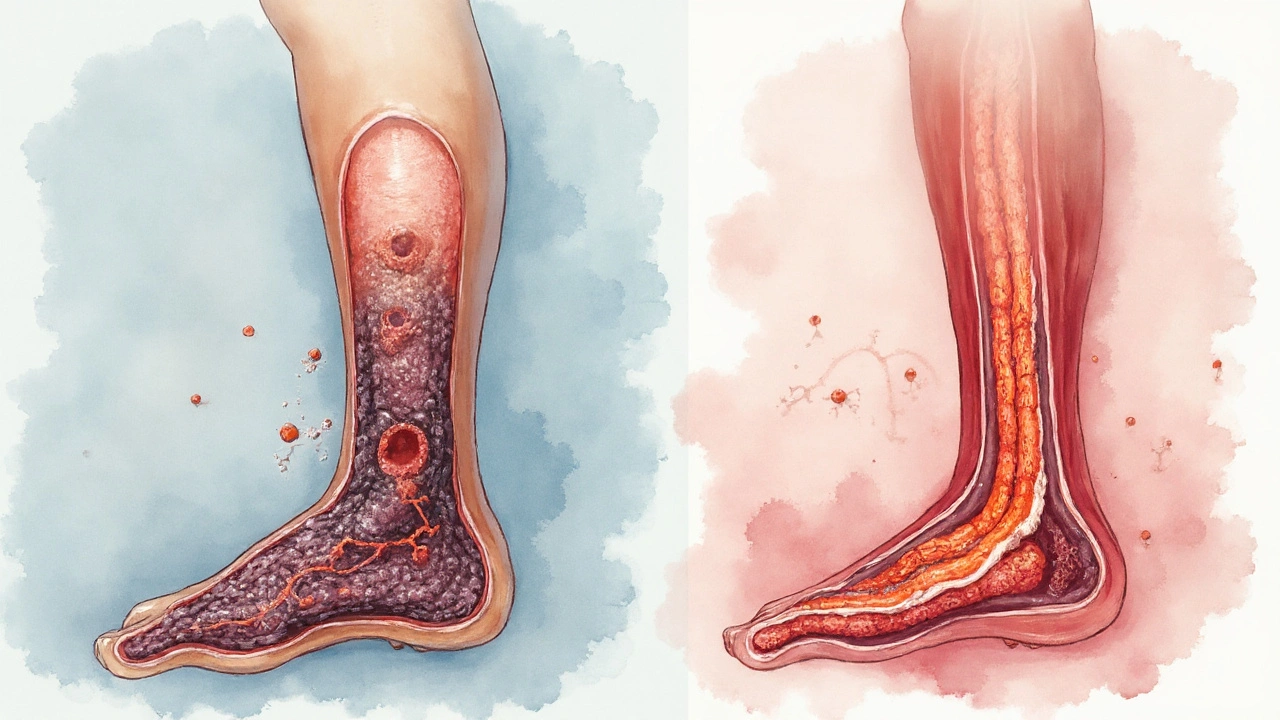

Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT) is a medical condition where a blood clot forms in the deep veins, most often in the legs. It can cause swelling, pain, and if untreated, the clot may travel to the lungs causing a pulmonary embolism. While many risk factors are known-like surgery, immobility, and genetics-Smoking is a preventable habit that directly influences the clotting cascade, endothelial health, and blood flow.

Why smokers should care about DVT

Each year, the World Health Organization estimates that over 10 million people worldwide develop DVT. In smokers, the incidence is up to 1.6‑times higher than in non‑smokers. A 2023 cohort study of 45,000 adults showed that current smokers had a 48% increased relative risk of a first DVT event compared with never‑smokers, even after adjusting for age, obesity, and activity level. The numbers aren’t just abstract-they translate into thousands of avoidable hospitalisations every year.

Biological pathways linking smoking to clot formation

The connection isn’t a single step; it’s a cascade of physiological changes. Below are the major mechanisms, each tied to a specific entity.

- Platelet activation: Nicotine and other tobacco alkaloids stimulate platelet receptors, making them stickier. Laboratory tests show a 20‑30% increase in platelet aggregation in regular smokers.

- Endothelial dysfunction: The inner lining of veins loses its ability to produce nitric oxide, a vasodilator that also inhibits clotting. Carbon monoxide from smoke binds to hemoglobin, reducing oxygen delivery and stressing the endothelium.

- Hypercoagulability: Smoking raises fibrinogen levels and shortens clotting time, creating a blood environment that favours clot formation.

- Inflammation: Chronic exposure to tobacco smoke triggers systemic inflammation, raising C‑reactive protein (CRP) levels, which correlate with higher DVT risk.

These pathways often act together, amplifying the overall risk. For instance, platelet activation can further injure the endothelium, while hypercoagulability ensures that any tiny clot will grow quickly.

Epidemiological evidence at a glance

Large‑scale studies consistently point to smoking as an independent DVT risk factor. Below is a snapshot of recent findings.

| Factor | Relative Risk (RR) | Typical Prevalence in Adults |

|---|---|---|

| Smoking | 1.48 | 20% (UK) |

| Obesity (BMI≥30) | 1.60 | 28% (UK) |

| Recent surgery (<6weeks) | 2.20 | 5% (hospital patients) |

| Hormone therapy (women) | 1.80 | 12% (post‑menopausal) |

While obesity and recent surgery carry higher relative risks, smoking is uniquely modifiable-quit today and you immediately start lowering that 1.48‑fold risk.

How quitting changes the numbers

The risk reduction timeline mirrors that of cardiovascular disease. Within 12months of cessation, platelet function returns to baseline, fibrinogen drops by about 15mg/dL, and CRP levels fall substantially. A longitudinal study of 8,000 former smokers found their DVT risk after 5years aligned with never‑smokers, indicating that the damage is largely reversible.

Prevention strategies tailored for smokers

Even if you’re not ready to quit, you can mitigate the added DVT danger.

- Stay active: Walking 30 minutes a day counteracts venous stasis, a key clot‑promoting factor.

- Hydration: Adequate fluid intake reduces blood viscosity.

- Compression therapy: Compression stockings exert graduated pressure, helping blood move upward toward the heart. Graduated 20‑30mmHg stockings are recommended for high‑risk individuals.

- Medical prophylaxis: If you’re undergoing surgery or prolonged travel, discuss Anticoagulant therapy (e.g., low‑molecular‑weight heparin) with your doctor.

- Quit smoking: Behavioural counselling, nicotine replacement, or prescription medications (varenicline, bupropion) increase quit rates by 30‑40% over unaided attempts.

Combining these actions slashes the cumulative risk. For example, a smoker who uses compression stockings during a long flight reduces the relative risk from 1.48 to roughly 1.10.

Related conditions worth knowing

Understanding DVT in the context of other vascular issues helps you see the bigger picture.

- Pulmonary embolism: The most dangerous sequel of DVT; a clot that reaches the lungs can be fatal.

- Peripheral artery disease: Shares similar risk enhancers like smoking and endothelial dysfunction.

- Cardiovascular disease: Smoking’s impact on atherosclerosis also predisposes patients to clot‑related events.

When you tackle smoking, you’re not just cutting DVT risk-you’re improving overall vascular health.

Take‑away checklist

- Recognise that smoking adds ~48% extra risk for a first DVT event.

- Know the four main mechanisms: platelet activation, endothelial dysfunction, hypercoagulability, inflammation.

- Use compression stockings and stay mobile, especially on long trips.

- Discuss anticoagulant prophylaxis with your clinician if you have surgery or prolonged immobility.

- Plan a quit strategy - the health payoff starts within weeks.

Frequently Asked Questions

Does occasional smoking increase DVT risk?

Even low‑level smoking raises platelet reactivity. A study of social smokers found a 12% higher DVT incidence compared with never‑smokers. The risk scales with frequency, so occasional use still matters.

Can e‑cigarettes cause the same clotting problems?

Vaping delivers nicotine, which alone triggers platelet activation. While the carbon monoxide load is lower, emerging data suggest a modest increase in fibrinogen levels, so the clot risk isn’t eliminated.

What symptoms should I watch for?

Typical DVT signs include swelling, warmth, and a tight‑feeling pain in the calf or thigh, often worse when standing. If you notice sudden shortness of breath or chest pain, seek emergency care-those could be a pulmonary embolism.

Is there a blood test that shows smoking‑related clot risk?

Elevated D‑dimer, fibrinogen, and C‑reactive protein can hint at a hypercoagulable state. However, no single test isolates smoking as the cause; clinicians evaluate the whole risk profile.

How long after quitting does my DVT risk normalize?

Most physiological changes reverse within 1-2years. After about five years of abstinence, epidemiological data show the DVT risk converges with that of never‑smokers.

Bansari Patel

September 22, 2025 AT 00:33Smoking is like an invisible tyrant that subtly reconfigures the very rivers of our blood, turning them into treacherous pathways for clots. It’s not just the nicotine that latches onto platelets, it’s the mindset that accepts a slow poison as a companion, which in philosophical terms betrays the virtue of self‑preservation. The cascade of platelet activation is a chain reaction reminiscent of a domino effect in a badly designed society. When you inhale, carbon monoxide steals oxygen, leaving the endothelial lining weak and defenseless, much like a wall eroded by constant winds. Hypercoagulability becomes the new normal, a state where the blood is primed for disaster as if waiting for a trigger. Inflammation flares up, CRP levels rise, and the body’s alarm system is constantly on high alert, similar to a city under perpetual siege. All these mechanisms intertwine, creating a perfect storm that makes DVT not a distant possibility but an impending certainty for smokers. The epidemiological data isn’t a mere statistic; it is a mirror reflecting a preventable tragedy. A 48% increase in risk is not just a number, it’s a call to conscience. The moral imperative to quit smoking is as clear as daylight, especially when thousands of hospital beds could be freed each year. You can argue that habits are hard to break, but philosophy teaches us that freedom is achieved through disciplined choice. Every cigarette is a small rebellion against your own vascular health, a rebellion that deserves to be quashed. The irony lies in the fact that something marketed as a stress reliever actually seeds the very stress of a potential fatal clot. The rational self, aware of these cascades, should act decisively. So, let the mind rise above the smoke, and let the veins breathe freely once more.

Rebecca Fuentes

October 3, 2025 AT 16:00Indeed, the mechanisms you outlined are well‑documented in the literature. The study you referenced, conducted in 2023, employed multivariate regression to adjust for confounders such as BMI and activity level, thereby strengthening the causal inference. Moreover, the relative risk of 1.48 aligns closely with meta‑analyses published in the Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis. From a public‑health perspective, these findings justify the inclusion of smoking cessation programs in DVT prevention strategies. It is also noteworthy that the endothelial dysfunction induced by carbon monoxide can be quantitatively measured via flow‑mediated dilation, offering a potential biomarker for early intervention. In sum, the evidence base robustly supports the claim that smoking is an independent risk factor for deep vein thrombosis.

Jacqueline D Greenberg

October 15, 2025 AT 05:46Wow, this really hits home. I’ve known a few friends who thought they were "fine" because they only smoked socially, but seeing these numbers makes me realize it’s a bigger threat than we thought. If you’re trying to quit, start small-maybe cut back to one less cigarette a day, then replace that habit with a walk or some deep breathing. It’s amazing how much better your legs feel when the blood flows smoother, and it’s a huge mental win when you see progress. Remember, you’re not alone in this; there are tons of support groups and apps that can keep you motivated. A healthier bloodstream means more energy for the things you love, whether that’s dancing, hiking, or just playing with your kids. Keep pushing, and don’t be too hard on yourself if you slip – it’s a journey, not a sprint.

Sharon Bruce

October 26, 2025 AT 18:33Totally agree, and as an American 🇺🇸, I think we should be proud of our advances in healthcare that can help people quit. 🚭 Even though I’m usually reserved, I can’t help but throw in a couple of emojis to emphasize how serious this is. 😷 Remember, each cigarette is a step away from the freedom we cherish.

True Bryant

November 7, 2025 AT 08:20Let's cut to the chase: the pathophysiology here is a textbook example of a pro‑thrombotic milieu amplified by exogenous toxins. When nicotine hijacks nicotinic acetylcholine receptors, you get heightened platelet aggregability-think of it as turning up the volume on a faulty speaker. The resultant hypercoagulable state is akin to a chemical cascade where fibrinogen spikes, shortening clotting times, a phenomenon well‑described in the coagulation cascade literature. You could argue that lifestyle interventions are merely adjuncts, but evidence‑based medicine tells us that smoking cessation is the cornerstone for mitigating DVT risk. In practice, clinicians should integrate smoking history into risk stratification models like the Caprini score. The drama of an embolism looming over a smoker is not hyperbole; it's a predictable outcome of disrupted hemostasis. So, buckle up, folks-if you’re still lighting up, you’re essentially rolling the dice with your circulatory system.

Danielle Greco

November 18, 2025 AT 22:06Spot on! 🌟