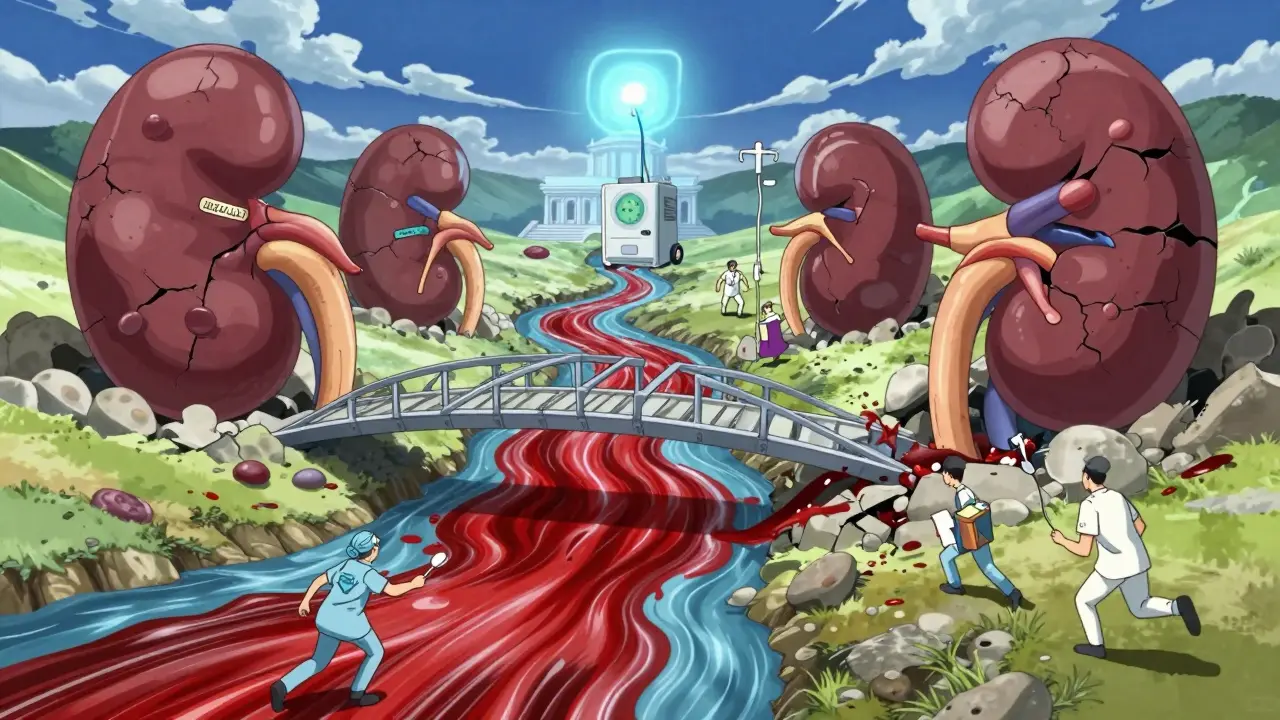

When your kidneys aren't working right, your body doesn't just struggle to filter waste-it starts losing control of the tiny charged particles that keep your heart beating, your muscles moving, and your nerves firing. Potassium, phosphate, and magnesium aren't just numbers on a lab report. They're the silent conductors of your body's electrical system. Get them wrong, and you could slip into a dangerous rhythm, stop breathing, or even have a cardiac arrest-without warning.

Why These Three Matter More Than You Think

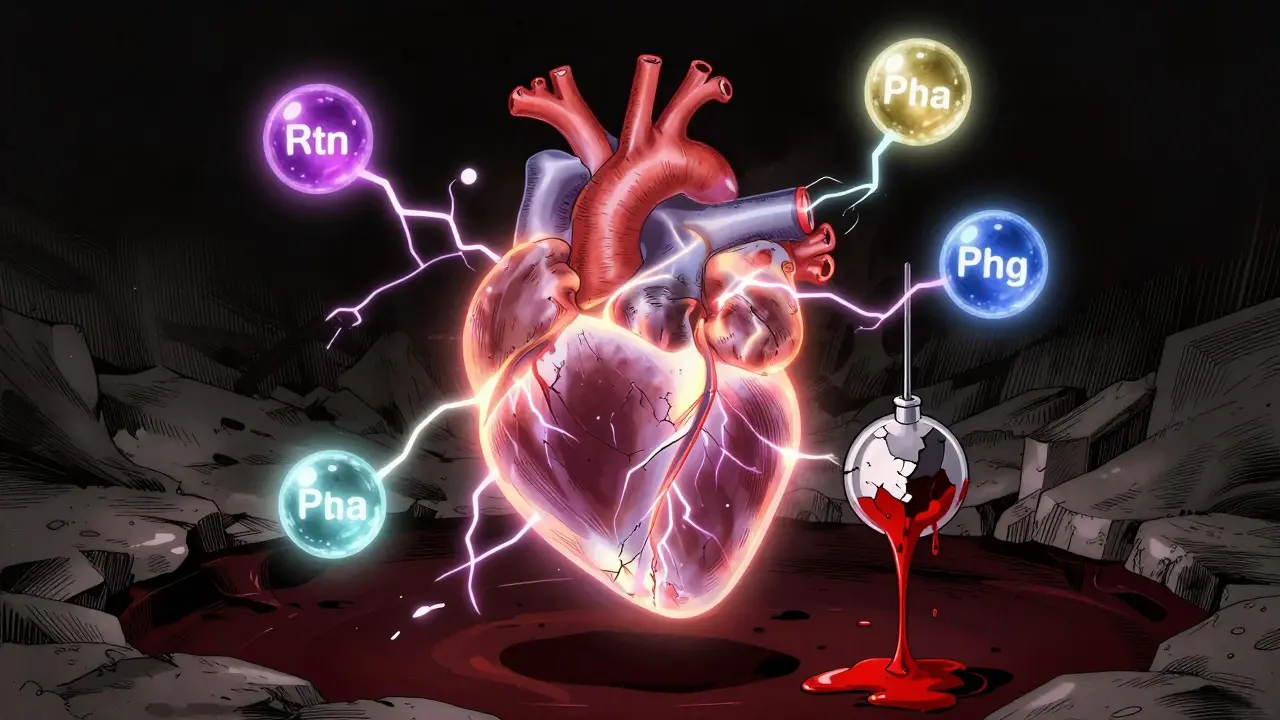

Potassium keeps your heart rhythm steady. Too little, and your heart might skip beats or go into fibrillation. Too much, and it can stop entirely. Phosphate fuels your cells. Without enough, your lungs can’t expand properly, your muscles weaken, and your brain fogs over. Magnesium? It’s the unsung hero that lets potassium and calcium do their jobs. If magnesium is low, giving potassium won’t fix anything. It’s like trying to start a car with a dead battery-even if you have gas, nothing happens.

Normal ranges are tight: potassium between 3.2 and 5.0 mEq/L, magnesium between 1.7 and 2.2 mg/dL, and phosphate between 2.5 and 4.5 mg/dL. But the real danger kicks in at the edges. A potassium level below 3.0 or above 6.5? That’s an emergency. Magnesium under 1.0? You’re at risk for seizures and arrhythmias. Phosphate under 1.0? Your body can’t make energy anymore. These aren’t just lab quirks-they’re red flags.

The Hidden Link Between Magnesium and Potassium

Here’s what most clinicians miss: you can’t fix low potassium if magnesium is also low. It’s not a coincidence. Low magnesium causes your kidneys to keep spitting out potassium, no matter how much you give. That’s why hypokalemia often doesn’t respond to potassium pills or IVs-it’s because the magnesium problem is still there.

Studies show that in patients with heart failure or on diuretics, up to 60% of those with low potassium also have low magnesium. And when both are down, the chance of dangerous heart rhythms jumps dramatically. The European Society of Cardiology and the American Heart Association both now say: check magnesium before you treat potassium. Always. If magnesium is below 1.8 mg/dL, give it first-usually 4 grams IV over an hour. Only then should you think about potassium.

It’s not just theory. At Vanderbilt University Medical Center, they saw a 21% drop in persistent hypokalemia after making magnesium replacement mandatory before potassium therapy. That’s not a small win. That’s life-saving.

How to Correct Low Potassium-Safely

When potassium drops below 3.0 mEq/L, you need to act. But how you give it matters. Giving too fast can burn veins, trigger arrhythmias, or even stop the heart.

- For mild cases (3.0-3.2 mEq/L): oral potassium chloride, 20-40 mEq per day in divided doses. Don’t crush extended-release pills-they’re designed to release slowly.

- For moderate (2.5-2.9 mEq/L): IV potassium at 10 mEq/hour max through a peripheral line. Never rush it.

- For severe (<2.5 mEq/L) or with ECG changes: central line, up to 40 mEq/hour, with continuous ECG monitoring. Always pair it with magnesium if levels are low.

Each 20 mEq of IV potassium raises serum levels by about 0.25 mEq/L. So if someone’s at 2.8 and you want to get them to 3.5, you’re looking at roughly 56 mEq total. That’s not one bag. That’s three hours of careful infusion.

And don’t forget to check levels again. After treatment, monitor potassium at 1 hour, 2 hours, 4 hours, 6 hours, and 24 hours. Levels can swing fast. A patient might look fine at 2 hours, then crash at 6 because their body’s still leaking potassium through the kidneys.

When Potassium Goes Too High-The Real Emergency

High potassium-hyperkalemia-is what kills people in the ER. Levels above 6.5 mEq/L with ECG changes (peaked T waves, widened QRS, flattened P waves)? That’s not a slow decline. That’s a ticking clock.

The protocol is strict, and timing is everything:

- Give calcium gluconate (10-20 mL of 10% solution) over 5-10 minutes. This doesn’t lower potassium-it protects the heart. Think of it as a shield.

- Then, shift potassium into cells with insulin and glucose: 10 units of regular insulin with 50 grams of dextrose. Works in 15-30 minutes.

- Next, bind the excess. Newer agents like sodium zirconium cyclosilicate and patiromer (approved by NICE in early 2023) are safer and more effective than old-school kayexalate. They grab potassium in the gut and flush it out.

- If the patient has kidney failure, or potassium stays above 7.0 despite all this? Dialysis. Now.

Never skip calcium. Even if the ECG looks fine, assume the worst. And don’t wait for repeat labs. If the patient has chest pain, palpitations, or sudden weakness after starting an ACE inhibitor or NSAID-treat like it’s hyperkalemia until proven otherwise.

Phosphate: The Forgotten Player in Critical Illness

Phosphate doesn’t get much attention until someone stops breathing. That’s when you realize their cells had no fuel left.

Hypophosphatemia is common in ICU patients. It shows up after refeeding syndrome, diabetic ketoacidosis, or after a big dose of IV iron. The FDA flagged ferric carboxymaltose in 2020 as a major cause-it pulls phosphate out of the blood and locks it away. Since then, many hospitals now check phosphate before and after iron infusions.

How to fix it?

- Mild cases (2.0-2.5 mg/dL): oral phosphate supplements, 8 mmol per dose, 3 times a day.

- Severe cases (<1.0 mg/dL): IV sodium or potassium phosphate. Dose is calculated in millimoles of elemental phosphorus-usually 7.5 mmol over 4-6 hours.

- Never give it too fast. Rapid infusion can cause calcium to drop, leading to tetany or cardiac arrest.

And watch for rebound. After correcting phosphate, levels can spike. That’s especially risky in kidney patients. Monitor every 4-6 hours until stable.

Hypermagnesemia: Rare, But Deadly

Too much magnesium? It’s rare-usually from overdose of antacids, laxatives, or IV magnesium in preeclampsia. But when it happens, it’s quiet and fast.

At 2.5-4.0 mg/dL, you see nausea, flushing, drowsiness. At 4.0-7.0 mg/dL, reflexes vanish. Above 7.0? You’re looking at respiratory paralysis and cardiac arrest.

First step: stop all magnesium. Then, give calcium gluconate-10-20 mL of 10% solution IV. Calcium reverses magnesium’s effects on nerves and muscles. If the patient is breathing poorly, support them with oxygen or intubation.

If kidneys are working, give furosemide to push out extra magnesium. If they’re not? Dialysis. No waiting. No second guesses.

Who’s at Risk-and How to Catch It Early

You don’t need to wait for someone to collapse. High-risk groups are predictable:

- People on diuretics (especially loop diuretics like furosemide)

- Patients with chronic kidney disease

- Those on ACE inhibitors, ARBs, or NSAIDs

- Malnourished or alcohol-dependent individuals

- Patients getting IV iron or insulin drips

- Anyone in the ICU

Screening is simple: a basic metabolic panel and magnesium level every 2-3 days in high-risk patients. At least once a week for those on long-term diuretics. Many hospitals now have automated alerts in their EMR systems that flag electrolyte trends-especially if potassium drops below 3.5 after starting a new medication.

Since 2021, teaching hospitals that added standardized order sets and clinical decision tools saw a 22.4% drop in electrolyte-related adverse events, according to JAMA Internal Medicine. That’s not magic. That’s systems.

What’s Changing Now

The field is moving fast. Point-of-care testing in emergency departments now gives potassium results in under 10 minutes-down from 45 minutes just a few years ago. That’s 37 minutes saved per case. Time that can mean the difference between life and death.

New potassium binders like sodium zirconium cyclosilicate are safer than old ones. They don’t cause constipation or bowel obstructions. And they work in hours, not days.

And soon? Personalized treatment. Phase 3 trials are testing genetic markers that predict how someone’s kidneys handle potassium. In the next two years, we may see algorithms that adjust doses based on your DNA-not just your lab values.

Bottom Line: Don’t Treat Numbers. Treat People.

Electrolytes aren’t abstract. They’re the rhythm of life. You don’t fix potassium without checking magnesium. You don’t replace phosphate without watching calcium. You don’t treat hyperkalemia without having calcium ready.

It’s not about memorizing ranges. It’s about understanding the connections. One imbalance sets off another. One missed step can cost a life.

Check magnesium before potassium. Know the emergency steps for high potassium. Screen the high-risk. Use new tools. And never, ever treat one electrolyte in isolation.

Can low potassium cause muscle weakness?

Yes. Low potassium disrupts nerve signals to muscles, leading to weakness, cramps, and even paralysis in severe cases. It’s one of the earliest signs of hypokalemia, especially in people on diuretics or with kidney disease.

Why is magnesium checked before potassium replacement?

Because low magnesium causes the kidneys to keep losing potassium, no matter how much you give. Without fixing magnesium first, potassium levels won’t rise-and the patient remains at risk for dangerous heart rhythms.

Can IV iron cause low phosphate?

Yes. Ferric carboxymaltose, a common IV iron product, has been linked to significant phosphate drops since a 2020 FDA safety alert. Always check phosphate levels before and after administration, especially in patients with malnutrition or chronic kidney disease.

What’s the fastest way to lower high potassium?

The fastest methods are insulin with glucose (shifts potassium into cells), calcium gluconate (protects the heart), and potassium-binding resins like sodium zirconium cyclosilicate. Hemodialysis is fastest for patients with kidney failure.

Is it safe to take magnesium supplements with kidney disease?

Not without supervision. Kidneys can’t clear excess magnesium, so supplements can build up and cause toxicity-even at normal doses. Always check serum magnesium before giving supplements to patients with reduced kidney function.

How often should electrolytes be checked in hospitalized patients?

At least every 2-3 days for all hospitalized patients. For those on diuretics, ACE inhibitors, or in the ICU, daily checks are recommended. After any electrolyte correction, repeat levels at 1, 2, 4, 6, and 24 hours to ensure stability.

Howard Esakov

January 28, 2026 AT 18:02Rhiannon Bosse

January 29, 2026 AT 09:33Bryan Fracchia

January 30, 2026 AT 10:41Lance Long

January 30, 2026 AT 13:15fiona vaz

January 31, 2026 AT 00:30Brittany Fiddes

February 1, 2026 AT 21:48Colin Pierce

February 2, 2026 AT 02:56Ambrose Curtis

February 3, 2026 AT 14:20