Antibiotic Alternatives: Practical Options for Modern Infections

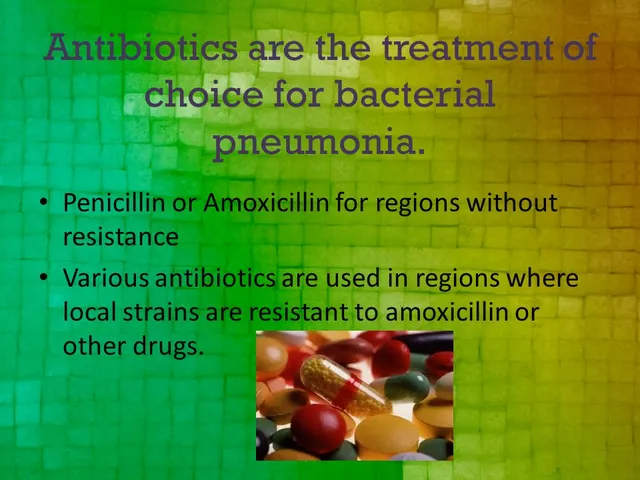

When looking at antibiotic alternatives, non‑antibiotic treatments that aim to fight bacterial infections while reducing reliance on traditional drugs, also known as non‑antibiotic therapies, you quickly see why they matter. Rising antibiotic resistance, the ability of bacteria to survive standard antibiotics forces clinicians and patients to consider other tools. Probiotic therapy, using live beneficial bacteria to outcompete harmful strains, offers a preventive angle, while phage therapy, the application of viruses that specifically kill bacteria provides a targeted, adaptable strike. Finally, natural antimicrobials, plant‑derived compounds like tea tree oil, garlic, or honey that inhibit bacterial growth give everyday options for mild infections. In short, the central topic encompasses microbial control, requires alternative agents, and influences public‑health strategies.

One of the biggest drivers for these alternatives is the global surge in antibiotic resistance. When bacteria acquire genes that neutralize drugs, standard treatments fail, leading to longer hospital stays and higher costs. That pressure has pushed research toward precision tools. For example, phage therapy taps into the natural predator‑prey relationship between bacteriophages and bacteria, allowing clinicians to select a virus that matches the offending strain. This specificity reduces collateral damage to the body’s normal flora, a common side‑effect of broad‑spectrum antibiotics. Meanwhile, probiotic therapy works on a different principle: by bolstering “good” microbes, it creates an environment where harmful bacteria struggle to establish themselves. Studies show that certain Lactobacillus strains can lower the incidence of urinary tract infections and even curb Clostridioides difficile overgrowth after antibiotic courses.

How Natural Antimicrobials Fit In

Natural antimicrobials sit at the intersection of traditional medicine and modern science. Compounds like allicin from garlic or methylglyoxal from Manuka honey have proven lab‑tested activity against a range of pathogens, including methicillin‑resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). These agents are often used topically for skin infections or as adjuncts in oral formulations for mild respiratory issues. Their appeal lies in low cost, wide availability, and a lower likelihood of driving resistance—though they’re not a cure‑all. Combining a natural antimicrobial with a short course of a narrow‑spectrum antibiotic can sometimes shorten treatment duration, which in turn lessens the selection pressure that fuels resistance.

Choosing the right alternative depends on the infection type, severity, and patient factors. For chronic sinusitis, a clinician might recommend a probiotic nasal spray alongside a short antibiotic stint. In cases of multi‑drug‑resistant wound infections, phage cocktails prepared from a local bacterial isolate can be life‑saving. And for everyday minor skin cuts, applying honey or tea tree oil can keep bacterial counts low without invoking the resistance cycle. The key is to view these options as part of an integrated treatment plan rather than isolated fixes.

Below, you’ll find a curated list of articles that break down each alternative in depth—comparisons, safety tips, cost considerations, and real‑world usage guides. Whether you’re a patient looking for DIY options or a professional seeking evidence‑based recommendations, the collection provides actionable insight to help you navigate the evolving landscape of infection control.

Ceclor CD (Cefaclor) vs Alternatives: A Detailed Comparison

A clear, side‑by‑side look at Ceclor CD (Cefaclor) versus common oral antibiotics, covering mechanisms, dosing, pros, cons, and how to pick the right one.

Detail

Cephalexin (Phexin) vs Top Antibiotic Alternatives: 2025 Comparison Guide

A 2025 guide comparing Cephalexin (Phexin) with top antibiotic alternatives, covering uses, side effects, cost, resistance and how to choose the right drug.

Detail