When your pharmacist hands you a generic pill instead of the brand-name drug your doctor prescribed, you might not think twice. But behind that simple swap is a detailed, science-backed system run by the FDA to make sure it’s safe. That system? Therapeutic equivalence codes. These two-letter codes - like AB, BC, or BX - tell pharmacists exactly which generic drugs can be swapped out without changing how well the medicine works or how safe it is.

What Therapeutic Equivalence Codes Really Mean

Therapeutic equivalence codes aren’t just labels. They’re the FDA’s official verdict on whether a generic drug can be substituted for the brand-name version - and whether that substitution will give you the same results. The FDA assigns these codes based on three things: pharmaceutical equivalence, bioequivalence, and clinical safety.Pharmaceutical equivalence means the generic has the same active ingredient, strength, dosage form (like tablet or capsule), and route of administration (like oral or injection) as the brand. But that’s not enough. Two pills can look identical and still behave differently in your body. That’s where bioequivalence comes in. The FDA requires generic manufacturers to prove their product releases the drug into your bloodstream at the same rate and amount as the brand. If it passes, the FDA gives it an ‘A’ rating.

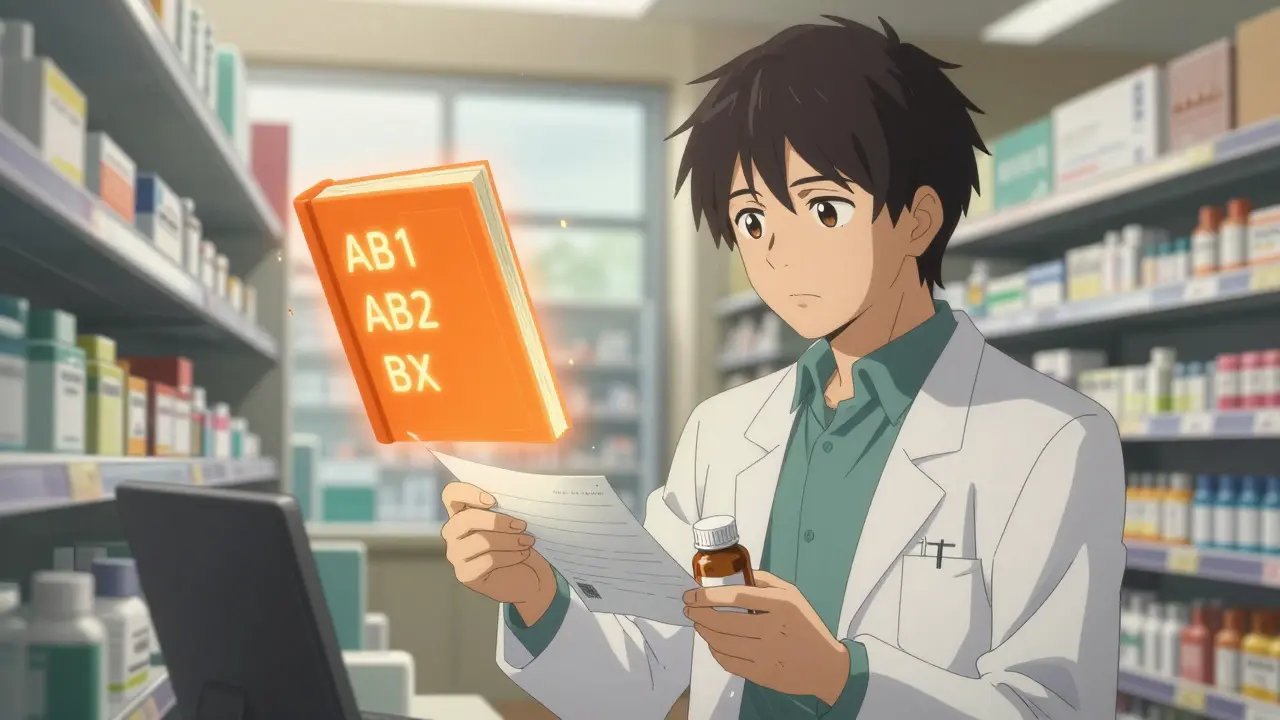

‘A’ means you can swap it freely. But not all ‘A’ codes are the same. You’ll see AB1, AB2, AB3, and AB4. These numbers tell you which brand-name drug the generic was tested against. If a drug has two different brand versions on the market, each with its own generic, the FDA uses these suffixes to avoid mixing the wrong ones. For example, AB1 might mean the generic was tested against Brand A, while AB2 was tested against Brand B. Mixing them could lead to unintended differences in how the drug works.

What the ‘B’ Codes Tell You (And Why They Matter)

If you see a ‘B’ in the code, it’s a red flag - but not always a dealbreaker. ‘B’ means the FDA hasn’t confirmed therapeutic equivalence. That doesn’t mean the generic is unsafe or ineffective. It means there’s not enough data to say for sure it works the same way.Some common ‘B’ codes include:

- BC - Extended-release products where bioequivalence is hard to prove

- BT - Topical creams or ointments with inconsistent absorption

- BN - Inhalers or nebulizer drugs with complex delivery

- BR - Suppositories or enemas meant for systemic effect

- BX - Not enough data to evaluate at all

These products are tricky. A cream might look identical on the label, but if the active ingredient doesn’t penetrate the skin the same way, it won’t work the same. Same with inhalers - even tiny differences in particle size can change how much drug reaches your lungs. The FDA knows this. That’s why it doesn’t automatically approve these as interchangeable.

Here’s the catch: some ‘B’-rated drugs are actually just as good as the brand. But because testing them is expensive and complicated, manufacturers often don’t submit enough data to get an ‘A’ rating. So pharmacists can’t substitute them without checking with the prescriber - even if the drug might work fine.

How Pharmacists Use the Orange Book

The FDA publishes all these codes in a document called the Orange Book - officially titled Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations. It’s been around since 1980, and it’s updated every month. Pharmacists rely on it daily. In fact, a 2022 survey found that 73% of community pharmacists consult the Orange Book at least once a week.When you pick up a prescription, the pharmacist checks the drug’s name, strength, and manufacturer. Then they look up the TE code. If it’s an ‘A’ rating, they can swap it without asking your doctor - and 49 out of 50 U.S. states allow this by law. If it’s a ‘B’, they’re required to either ask your doctor or leave it as-is, depending on state rules. Thirty-eight states require pharmacists to notify the prescriber before substituting a ‘B’-rated drug.

The system saves money. Generic drugs make up 90% of prescriptions filled in the U.S., but only 23% of total drug spending. That’s about $370 billion saved every year. The Orange Book is what makes that possible - it gives pharmacists the confidence to substitute safely.

Why Some Doctors Are Confused

Despite how well the system works for pharmacists, many doctors don’t fully understand it. A 2022 American Medical Association survey found that 42% of physicians are unsure what ‘B’ codes mean. Some think a ‘B’ means the drug is unsafe. Others assume it’s just as good as an ‘A’ and don’t realize substitution might be restricted.This confusion leads to real problems. In some cases, pharmacists refuse to substitute a ‘B’-rated drug even when it’s clinically appropriate - just to be safe. In others, doctors prescribe a brand-name drug thinking no generic exists, when one does - but it’s coded ‘B’ and they didn’t know.

It’s not the system’s fault. It’s a communication gap. The FDA’s codes are designed for pharmacists, not prescribers. But since doctors write the prescriptions, they need to understand the basics too. A simple note on the prescription - like “Do not substitute” - can override the TE code. But too often, that note is missing.

Where the System Falls Short

The TE code system works brilliantly for simple pills - immediate-release tablets or capsules with well-understood absorption patterns. But it struggles with complex products. Topical creams, inhaled drugs, injectables, and extended-release formulations don’t always behave the same way in the body, even if their chemical makeup matches.The FDA admits this. In its 2022 draft guidance, the agency acknowledged that standard bioequivalence tests - like measuring blood levels over time - don’t always capture how these complex drugs work. For example, a generic inhaler might release the same amount of drug, but if the spray pattern or particle size differs, it could land in the wrong part of the lung and be less effective.

That’s why the number of ‘B’-rated applications for complex generics rose 22% between 2018 and 2022. The FDA is working on better ways to test them - like using in vitro models or real-world data - and aims to reduce ‘B’ ratings for these products by 30% by 2027.

How This Compares to Other Countries

The U.S. is one of the few countries with a formal, color-coded system like this. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) doesn’t use codes at all. Instead, it publishes detailed scientific reviews for each generic application. That’s more thorough - but it’s not practical for daily pharmacy use. A pharmacist in Germany can’t flip through a 50-page report every time someone walks in.The FDA’s system is fast, simple, and built into state laws. That’s why it’s so effective. But it’s also why it needs updating. As more complex drugs come to market - like biosimilars and advanced inhalers - the old rules might not be enough.

What You Should Know as a Patient

You don’t need to memorize TE codes. But you should know this: if your generic looks different from last time, or if your doctor says “no substitutions,” it might be because of the TE code. Ask your pharmacist: “Is this an AB-rated generic?” If they say yes, you’re getting a drug that’s been proven to work the same. If they say it’s a ‘B’, ask why - and whether your doctor needs to approve the change.Don’t assume a cheaper generic is always interchangeable. Sometimes, it’s not because of quality - it’s because the science hasn’t caught up yet.

What’s Next for Therapeutic Equivalence

The FDA is moving toward more modern ways to evaluate complex drugs. Instead of relying only on blood tests, they’re exploring real-world evidence - like how patients actually respond in clinics - and advanced lab models that mimic how drugs behave in the body.They’re also expanding their Product-Specific Guidances - 1,850 as of 2023 - which give manufacturers clear instructions on how to prove bioequivalence for each drug. This helps more generics get ‘A’ ratings faster.

For now, the system works. It’s saved billions, kept patients safe, and kept generics flowing. But as medicine gets more complex, the codes will have to evolve too.

What does an AB rating mean for a generic drug?

An AB rating means the generic drug is therapeutically equivalent to the brand-name drug. It has the same active ingredient, strength, dosage form, and route of administration, and has passed FDA bioequivalence testing. Pharmacists can substitute it without needing the prescriber’s approval in most states.

Can I ask my pharmacist to switch me to a different generic if my current one has a B rating?

You can ask, but your pharmacist can’t automatically switch you. A ‘B’ rating means the FDA hasn’t confirmed therapeutic equivalence. Substitution may require your doctor’s approval, depending on your state’s laws. Some ‘B’-rated drugs are still safe and effective - but the evidence isn’t strong enough for automatic substitution.

Why do some generic drugs have different codes like AB1, AB2, or AB3?

These suffixes indicate which brand-name drug the generic was tested against. If multiple brand versions exist for the same drug, each may have its own set of generics. AB1 means the generic was tested against the first reference drug, AB2 against the second, and so on. Mixing generics with different suffixes could lead to unintended differences in how the drug works in your body.

Are over-the-counter (OTC) drugs given therapeutic equivalence codes?

No. The FDA only assigns therapeutic equivalence codes to prescription drugs. OTC medications are not evaluated for substitution using the Orange Book system, even if they have generic versions.

How often is the Orange Book updated?

The Orange Book is updated monthly. New drug approvals, code changes, and withdrawn products are added each month. Pharmacists and healthcare providers rely on these updates to ensure they’re using the most current substitution information.

Jessie Ann Lambrecht

January 7, 2026 AT 18:24Finally, someone explains this stuff without jargon. I’m a pharmacist in Ohio and I use the Orange Book every damn day. AB-rated generics? Swappable without a second thought. B-rated? I call the doctor. Simple. The system works-until doctors don’t read the damn codes.

Kyle King

January 8, 2026 AT 19:46Yeah right. The FDA’s just a puppet for Big Pharma. AB codes? More like ‘Approved By’-as in, approved because the generic maker paid the right lobbyists. I’ve seen people get sick switching generics. They just don’t wanna admit it. They’d rather save $3 than keep you alive.

Emma Addison Thomas

January 10, 2026 AT 05:49Interesting. In the UK, we just trust the prescriber’s judgment and the pharmacy’s clinical knowledge. No color codes, no Orange Book-just professional discretion. It’s slower, sure, but it avoids the illusion of binary safety. We don’t need a letter to tell us what’s equivalent.

Aparna karwande

January 10, 2026 AT 17:39How can Americans still believe in this bureaucratic charade? You let a government agency assign letters to your medicine like it’s a movie rating? In India, we don’t need a code to know if a pill works-we know because people live or die from it. This system is a luxury of privilege. And don’t get me started on how ‘AB1’ and ‘AB2’ are just corporate loopholes dressed as science.

They call it ‘therapeutic equivalence’-but it’s really just regulatory theater. You think your body doesn’t notice the difference in fillers? In coating? In dissolution rate? Wake up. The FDA doesn’t test what matters. They test what’s easy to measure.

And yet you people cheer like this is progress. You’re not saving money-you’re gambling with your health. And for what? A 23% discount on a drug that could be making you sicker?

Stop calling it ‘safe.’ Call it ‘statistically acceptable.’ There’s a difference. And if you’re lucky, you’ll never be the one who finds out.

Mina Murray

January 11, 2026 AT 02:24Wait so OTC drugs don’t get codes? That’s wild. So if I buy ibuprofen from Walmart vs. CVS, they could be totally different and I’d never know? That’s not a coincidence-this is how they control the market. They want you to think generics are safe so you’ll take the cheap ones, but only for prescriptions. OTC? No oversight. That’s how you get people with kidney damage from ‘generic’ painkillers.

And don’t even get me started on the ‘AB’ suffixes. AB1, AB2… it’s like they’re coding for corporate alliances. I bet the same companies own the brand and the generic. It’s all one big cartel.

Vince Nairn

January 11, 2026 AT 11:04Look I get why the system’s confusing. I’m a nurse and I used to think B meant bad. Turns out it just means ‘we haven’t tested it enough yet.’ That’s not a red flag, it’s a caution light. Most B-rated stuff is fine-just needs more data. But yeah, doctors need to learn this stuff. I’ve seen them write ‘no substitution’ on prescriptions for AB-rated drugs. It’s like they’re scared of their own job.

Also, props to pharmacists. They’re the real MVPs here. They’re the ones holding the line between your wallet and your health.

Alex Danner

January 11, 2026 AT 22:31One thing no one talks about: the cost of testing. To get an AB rating, a generic company has to run clinical trials that cost millions. For a $2 pill? That’s not a business-it’s suicide. So they go for the B rating, save the cash, and sell it anyway. Pharmacists know this. Patients don’t. That’s the real gap.

And the FDA knows it too. That’s why they’re pushing for better models-like simulating drug absorption in labs instead of relying on blood tests. It’s expensive, but cheaper than running 500 human trials for every cream and inhaler.

Progress is slow, but it’s happening. The system’s not perfect, but it’s the best we’ve got. And it’s saved hundreds of billions. That’s not nothing.

Anastasia Novak

January 13, 2026 AT 03:24Let’s be real-this whole system is a performance. The Orange Book? A 40-year-old PDF that’s barely updated. The FDA’s ‘science’? Based on blood levels from 12 healthy young men in a lab. You think your 72-year-old diabetic grandma with kidney issues absorbs drugs the same way? Please. The code says AB, so you get it. But your body? It’s screaming. And nobody’s listening.

They call it ‘equivalence.’ I call it ‘convenient approximation.’ And the fact that we treat it like gospel? That’s the real tragedy. We’ve outsourced our health to a spreadsheet.

And now we’re doing it with biosimilars too. Same script. Same lies. Same people getting sicker while someone in a suit checks a box.

Rachel Steward

January 13, 2026 AT 17:54Here’s the truth they won’t tell you: the FDA doesn’t care if your generic works the same. They care if it’s close enough to pass a statistical threshold. 80-125% bioequivalence? That’s not equivalence-that’s a tolerance range wide enough to drive a truck through. One generic might give you 90% of the drug. Another might give you 120%. Both are ‘AB.’ Both are legal. Both can kill you if you’re sensitive.

And the suffixes? AB1, AB2? That’s not science. That’s corporate insurance. If you get AB1 and your body reacts badly, they’ll say ‘you were on the wrong version.’ No accountability. Just a letter.

Doctors don’t understand it because they’re not trained to. Pharmacists don’t question it because they’re paid to dispense, not to diagnose. And you? You just swallow the pill and hope.

This isn’t healthcare. It’s a numbers game with your life as the bet.