Antibiotics are one of the most important medical breakthroughs in human history. Before they existed, even minor cuts or sore throats could turn deadly. Today, they save millions of lives every year by targeting bacterial infections - not viruses, not fungi, not parasites. If you’ve ever taken amoxicillin for a sinus infection or ciprofloxacin for a UTI, you’ve used one of these powerful tools. But not all antibiotics work the same way. Understanding how they function helps you make smarter decisions about your health - and know why your doctor chooses one over another.

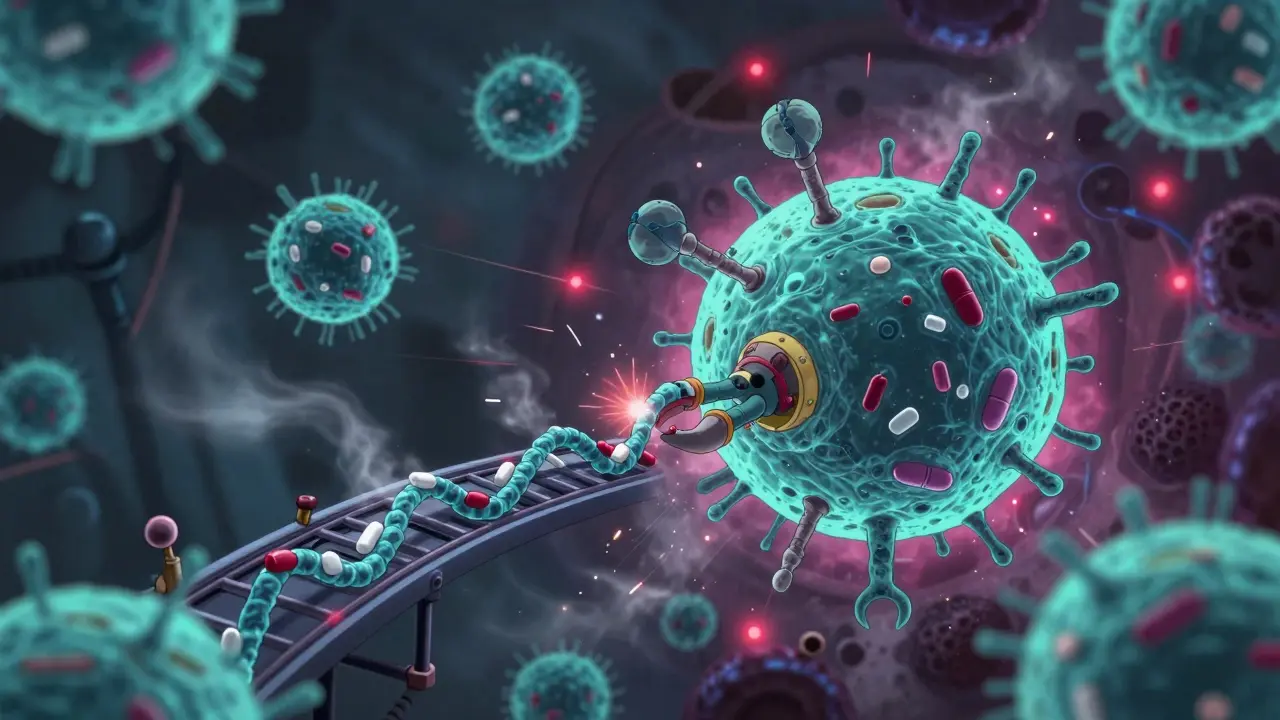

How Antibiotics Kill or Stop Bacteria

Antibiotics don’t just randomly attack bacteria. They target very specific parts of bacterial cells that human cells don’t have. This is what makes them safe for us - most of the time. There are four main ways antibiotics work:

- Break down the bacterial cell wall - this causes the cell to burst

- Stop protein production - bacteria can’t build the tools they need to survive

- Block DNA replication - bacteria can’t copy themselves to multiply

- Damage the cell membrane - this leaks vital contents out of the cell

Some antibiotics kill bacteria outright (bactericidal), like penicillin. Others just stop them from multiplying (bacteriostatic), like tetracycline. Your immune system then clears the rest. Both types are useful - it just depends on the infection and your body’s ability to fight back.

Beta-Lactams: The Cell Wall Breakers

The most widely used class of antibiotics is the beta-lactams. This group includes penicillins (like amoxicillin), cephalosporins (like cefalexin), and carbapenems (like meropenem). Their secret weapon? A four-sided ring structure called the beta-lactam ring. This ring mimics a part of the bacterial cell wall, tricking the bacteria into letting it in.

Once inside, the antibiotic binds to proteins called penicillin-binding proteins (PBPs). These proteins normally help build and repair the cell wall. When blocked, the wall becomes weak and full of holes. Because bacteria live in a watery environment, water rushes in, and the cell bursts. It’s like poking a balloon underwater - inevitable.

Cephalosporins come in four generations:

- First-generation (e.g., cefazolin): Best for skin and soft tissue infections caused by common Gram-positive bugs like Staphylococcus.

- Second-generation (e.g., cefuroxime): Adds coverage against some Gram-negative bacteria like E. coli and H. influenzae.

- Third-generation (e.g., ceftriaxone): Strong against tough Gram-negatives like Pseudomonas and Neisseria. Often used in hospital settings for pneumonia or meningitis.

- Fourth-generation (e.g., cefepime): Broadest coverage - works against both Gram-positive and resistant Gram-negative strains.

But there’s a catch. Many bacteria produce enzymes called beta-lactamases that chop up the beta-lactam ring. That’s why amoxicillin often gets paired with clavulanic acid - the latter blocks the enzyme, letting the antibiotic work.

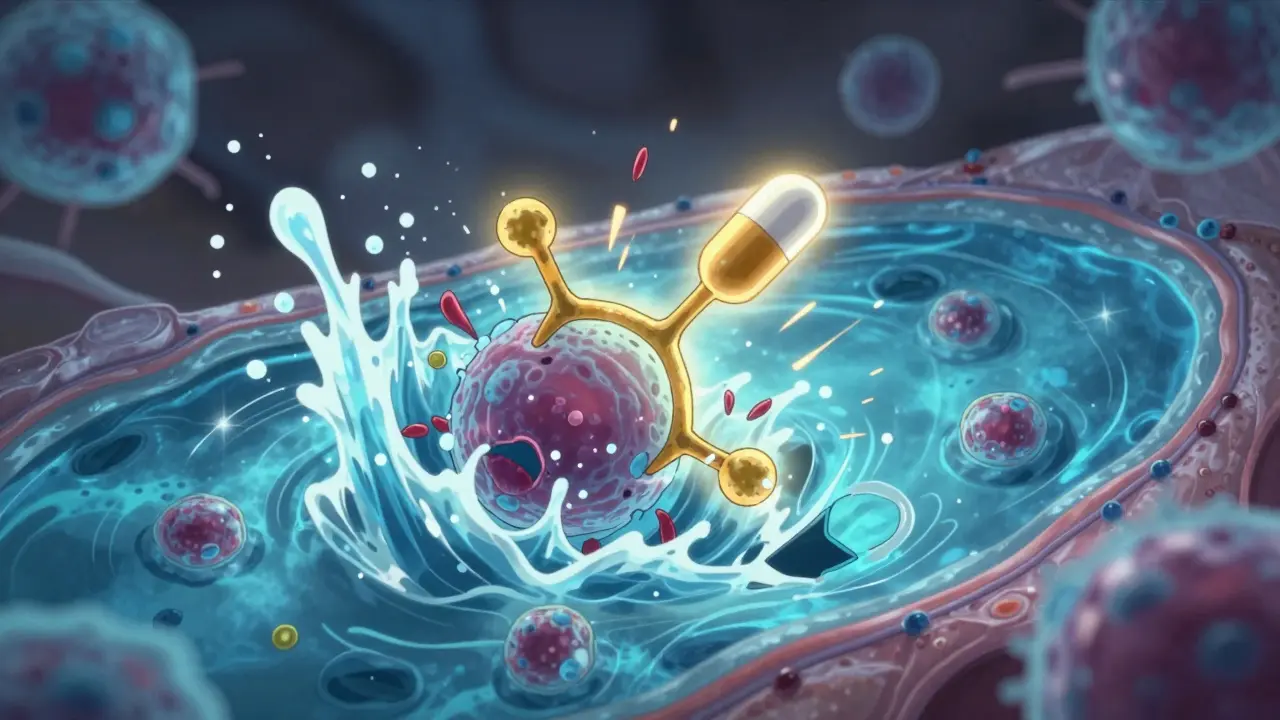

Protein Synthesis Inhibitors: Shutting Down the Factory

Bacteria need proteins to survive. They build them using tiny machines called ribosomes. Antibiotics in this class slip into those ribosomes and jam the process. Three major groups do this:

- Macrolides (e.g., azithromycin): Bind to the 50S ribosomal subunit. Used for respiratory infections, Lyme disease, and some STIs. Often chosen for people allergic to penicillin.

- Tetracyclines (e.g., doxycycline): Attach to the 30S subunit. Effective against acne, tick-borne illnesses like Rocky Mountain spotted fever, and even some types of pneumonia. But they stain developing teeth - so avoid in kids under 8.

- Aminoglycosides (e.g., gentamicin): Also bind to the 30S subunit, but they cause the ribosome to misread genetic code. This creates broken proteins that poison the cell. Used in serious infections like sepsis - but they can damage kidneys and hearing. That’s why they’re usually given in hospitals, not at home.

Then there’s linezolid, a newer drug in the oxazolidinone class. It blocks protein synthesis at the very start - before the ribosome even assembles. It’s one of the few antibiotics that works against vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE) and some MRSA strains. Because it’s synthetic - made entirely in a lab - it’s harder for bacteria to evolve resistance to it.

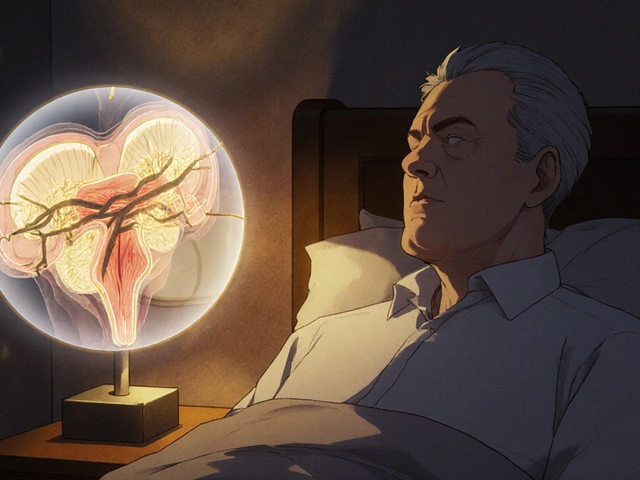

DNA Replication Blockers: Fluoroquinolones

Fluoroquinolones - like ciprofloxacin and levofloxacin - are powerful, broad-spectrum antibiotics. They stop bacteria from unwinding and copying their DNA. They do this by targeting two enzymes: DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV. Without these, the bacteria can’t divide.

These drugs are great because they penetrate deep into tissues - bones, lungs, even the prostate. That’s why they’re used for complicated UTIs, kidney infections, and certain types of pneumonia.

But they come with serious risks. The FDA added black box warnings in 2022 because fluoroquinolones can cause tendon ruptures, nerve damage, and even long-term muscle weakness. They’re now reserved for infections with no safer alternatives. For example, if you have a severe UTI and penicillin or trimethoprim won’t work, then ciprofloxacin might be the last option.

Other Important Classes

Not all antibiotics fit neatly into those four categories. Here are two others you should know:

- Sulfonamides (e.g., sulfamethoxazole): These block folate production - a vitamin bacteria need to make DNA and proteins. They’re rarely used alone anymore because resistance is high. But they’re still effective when combined with trimethoprim (as co-trimoxazole) for pneumonia caused by Pneumocystis jirovecii, especially in people with weakened immune systems.

- Nitroimidazoles (e.g., metronidazole): These work only in low-oxygen environments. That’s why they’re perfect for anaerobic infections - like abscesses in the abdomen or dental infections. They also treat parasitic infections like giardia. But if you drink alcohol while taking metronidazole, you’ll get a nasty reaction: nausea, vomiting, flushing. It’s not just uncomfortable - it’s dangerous.

Why Resistance Is Growing - And What It Means

Every time you take an antibiotic, you’re putting pressure on bacteria. The ones that survive - because they have a mutation or a shield - pass on their resistance. Over time, that makes antibiotics useless.

Right now, over 50% of E. coli strains in 72 countries are resistant to fluoroquinolones. In hospitals, carbapenem-resistant bacteria are spreading fast. These are called “superbugs” - and they’re terrifying because we have almost no drugs left to treat them.

One big reason? Overuse. About 30% of outpatient antibiotic prescriptions in the U.S. are unnecessary - often given for colds or flu, which are viral. Antibiotics don’t work on viruses. Taking them anyway just helps resistant strains grow.

Doctors are now using tools like procalcitonin tests to tell if an infection is bacterial or viral. If procalcitonin levels are low, it’s likely viral - and antibiotics aren’t needed. This cuts down misuse by 23% in respiratory infections.

What’s Next? New Drugs and New Thinking

There’s hope. In 2019, the FDA approved ceftiderocol, a new cephalosporin that tricks bacteria into pulling it inside by pretending to be iron. This lets it bypass the usual resistance shields. In trials, it cured 75% of patients with infections that were untreatable by other antibiotics.

Phage therapy - using viruses that infect only bacteria - is now in Phase III trials. Early results show promise for hard-to-treat Pseudomonas infections. The European Medicines Agency has already created a special approval path for these therapies.

But money is still a problem. Developing a new antibiotic costs over $1.5 billion. Yet companies only make about $17 million per year in sales. That’s why the UK started a “Netflix model” in 2023: pay hospitals a flat fee of £76 million a year for access to new antibiotics - no matter how many they use. This way, doctors can save these drugs for emergencies, and drugmakers get paid fairly.

When to Use Antibiotics - And When Not To

Antibiotics are lifesavers - but only when used right. Here’s when they help:

- Strep throat (confirmed by test)

- Urinary tract infections

- Pneumonia (bacterial)

- Skin abscesses

- Sinus infections that last more than 10 days

And here’s when they don’t:

- Colds

- Flu

- Sore throats without fever or swollen tonsils

- Most coughs

- Runny noses

If you’re unsure, ask your doctor: “Is this infection bacterial? Do we have proof?” Don’t pressure them to prescribe - you’re helping them make a better choice.

Prajwal Manjunath Shanthappa

February 3, 2026 AT 15:36Wendy Lamb

February 4, 2026 AT 02:52Ed Mackey

February 5, 2026 AT 15:13Alex LaVey

February 6, 2026 AT 10:41Jesse Naidoo

February 8, 2026 AT 09:26Daz Leonheart

February 9, 2026 AT 17:59Amit Jain

February 9, 2026 AT 18:23Roshan Gudhe

February 10, 2026 AT 10:49Rachel Kipps

February 11, 2026 AT 06:15