When a brand-name drug loses patent protection, the race to bring the first generic version to market isn’t just about speed-it’s about survival. But here’s the twist: the company that wins that race doesn’t always win the market. That’s because the brand-name drugmaker can hit back with something called an authorized generic, and it doesn’t play by the same rules.

What’s the difference between a first generic and an authorized generic?

A first generic is made by a company that challenges the brand’s patent, goes through the full FDA approval process with an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA), and gets the legal right to be the only generic on the market for 180 days. This exclusivity is the whole point of the Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984-it’s meant to reward companies willing to take on the cost and risk of suing big pharma to get cheaper drugs to patients.

An authorized generic is different. It’s made by the same company that makes the brand-name drug-or by a partner they’ve given permission to. It’s chemically identical, often made in the same factory, and sold under a generic label. But here’s the key: it doesn’t need an ANDA. It uses the brand’s existing New Drug Application (NDA), so it can launch anytime, even before the first generic hits shelves.

Think of it like this: the first generic is the underdog who broke into the race. The authorized generic is the favorite who just slipped into the starting line wearing the same shoes.

Why timing matters more than you think

The 180-day exclusivity window for first generics isn’t just a reward-it’s a financial lifeline. During that time, the first generic typically captures 70% to 90% of the market. For a blockbuster drug like Lyrica (pregabalin), that can mean hundreds of millions in revenue.

But if the brand company launches its authorized generic on the same day the first generic enters, everything changes. Suddenly, the market splits. Instead of one company taking 80%, you’ve got two. The first generic’s share drops to 45% or lower. Revenue plummets.

Research from Health Affairs shows that 73% of authorized generics launch within 90 days of the first generic’s approval. Over 40% launch on the exact same day. That’s not coincidence. That’s strategy.

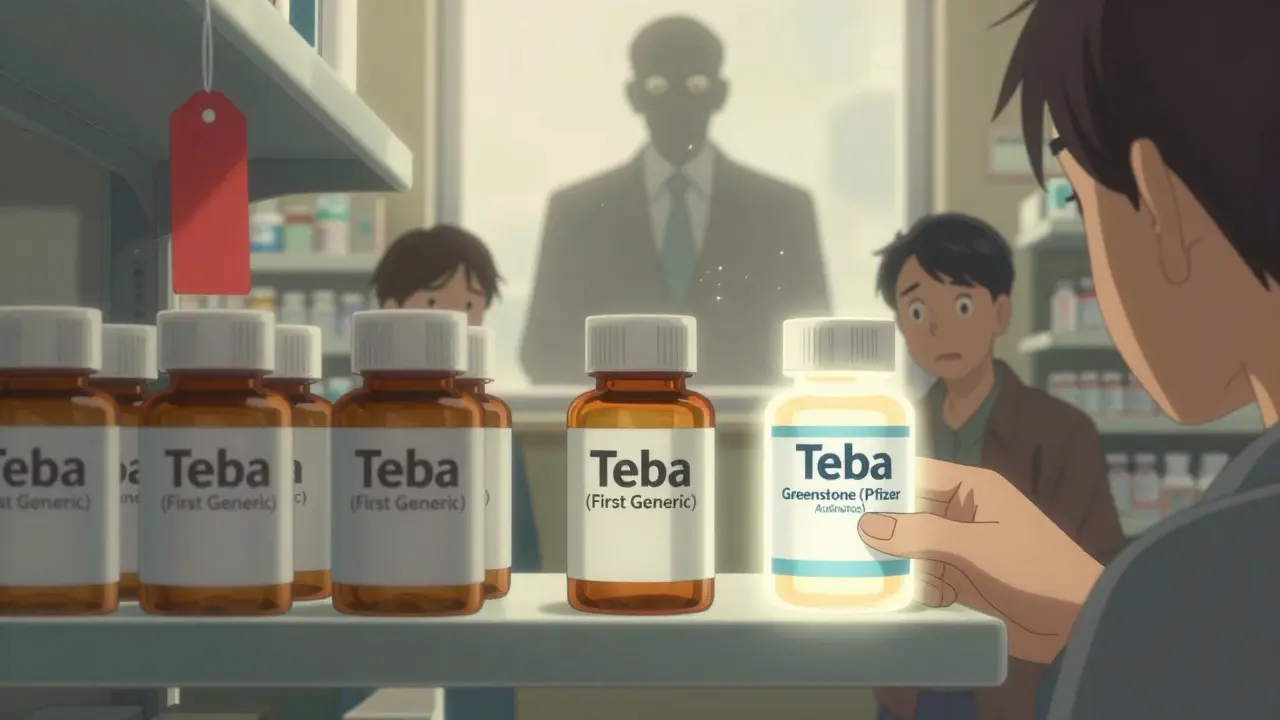

Take Pfizer and Teva in 2019. Teva got the green light to sell the first generic version of Lyrica. Hours later, Pfizer launched its own authorized generic through Greenstone LLC. Within weeks, Teva’s market share was cut in half. The price drop-the whole point of generics-stayed at 65%, not the 80-90% you’d expect with real competition.

How authorized generics bypass the rules

First generics have to prove they’re bioequivalent to the brand drug. That means clinical testing, paperwork, FDA reviews that can take 10 months to over three years. They spend $5 million to $10 million per drug. They risk losing lawsuits. They wait years for a shot at the prize.

Authorized generics? They skip all that. They don’t need to prove anything new. They just need a green light from the brand company. The FDA doesn’t require a separate application. The drug is already approved. All they need is a label change and a distributor.

This isn’t a loophole-it’s built into the system. And brand companies know it. They watch the patent challenges like a chess game. When they see a first generic about to win, they pull the trigger on their authorized version. It’s fast, legal, and devastating.

The impact on prices-and your wallet

Generics are supposed to slash prices. And they do-when they’re the only option. But when an authorized generic enters during the first generic’s exclusivity, prices don’t fall as far.

RAND Corporation found that when authorized generics show up early, price drops average only 65-75%, not the 80-90% seen when multiple traditional generics enter later. That might sound small, but for a drug like Eliquis (apixaban), which costs $500 a month, that 15% difference means thousands of dollars in extra costs per patient per year.

And it adds up. The healthcare system loses billions. Patients pay more. Insurance companies pay more. Taxpayers pay more through Medicare and Medicaid.

The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 tried to address this. It explicitly said authorized generics don’t count as "generic competitors" when the government negotiates drug prices for Medicare. That’s a quiet acknowledgment: these aren’t real competitors. They’re brand-name drugs in disguise.

Who wins? Who loses?

On the surface, authorized generics look like a win for consumers. More options. Lower prices. Right?

Not so fast.

The Association for Accessible Medicines (AAM) argues they speed up access. And yes, they do get cheaper versions out faster. But they do it by crushing the incentive for real generic competition. Why would a company invest millions to challenge a patent if the brand can just drop in its own version and steal the market?

Real generic manufacturers are getting squeezed. Mid-sized companies report their profitable window has shrunk from 180 days to just 45-60 days. Some have stopped filing patent challenges altogether. That means fewer players in the game. Fewer challengers. Fewer long-term price drops.

The big winners? The brand-name companies. They keep control. They protect their profits. And they do it without breaking any rules.

What’s happening now-and what’s next

Cardiovascular, nervous system, and metabolic drugs are the most common battlegrounds. Drugs like Jardiance, Eliquis, and Neurontin have all seen this play out.

Companies are adapting. Some now build "dual-path" strategies: they prepare for both the first generic launch and the risk of an authorized generic. Others focus on niche drugs where brand companies don’t bother to fight back. A few are even partnering with brand manufacturers to become their authorized generic partner-turning the tables.

By 2027, authorized generics are expected to make up 25-30% of all generic prescriptions-up from 18% in 2022. That’s not growth. That’s a shift in power.

The FDA approved 80 first generics in 2017 after reforms sped up reviews. But that progress is being undone by strategic authorized generic launches. Less than 10% of generic applications get approved on the first try. The system is slow for challengers, but lightning-fast for insiders.

What does this mean for patients?

It means the drug you get at the pharmacy might look like a generic-but it’s still the same company making the brand drug. You’re not getting true competition. You’re getting a controlled version of it.

It also means price drops aren’t guaranteed. Even when a drug goes generic, your copay might not drop as much as you expect. And if you’re on Medicare, the government might not even count that authorized generic when negotiating prices.

The system was built to lower costs and increase access. But over time, it became a tool for the biggest players to protect their profits under the guise of competition.

Ashok Sakra

January 21, 2026 AT 02:57Roisin Kelly

January 21, 2026 AT 16:57Kevin Narvaes

January 22, 2026 AT 10:24Jarrod Flesch

January 23, 2026 AT 03:18Barbara Mahone

January 23, 2026 AT 23:42Kelly McRainey Moore

January 25, 2026 AT 04:02michelle Brownsea

January 25, 2026 AT 19:59lokesh prasanth

January 26, 2026 AT 13:12Malvina Tomja

January 26, 2026 AT 23:05Yuri Hyuga

January 28, 2026 AT 16:03MARILYN ONEILL

January 28, 2026 AT 23:48Steve Hesketh

January 29, 2026 AT 16:27shubham rathee

January 30, 2026 AT 14:34Sangeeta Isaac

February 1, 2026 AT 11:42Alex Carletti Gouvea

February 2, 2026 AT 09:30